|

Search this site for keywords or topics..... | ||

Custom Search

| ||

Colony Rabbits

The above photo is from one of our first experiments with colony rabbits. The nine young rabbits are an entire litter being grown out in what started as one colony. The four rabbits at the far right of the pen are the males, which were separated out at two months. It's hard to see but there is a single feeder and water bottle at each end of the pen, making daily chores a snap. The pen material was 2"x2" woven fencing, cut to size. The second pen visible in the lower right was a different design, using different materials, which proved to be too time-consuming to build and too heavy to conveniently move. All the pens are in a field shelter made by draping a blue tarp over a PVC pole frame. I wince when I see this picture because we've learned so much since then about what works and what doesn't. But it illustrates one of many possibilities.

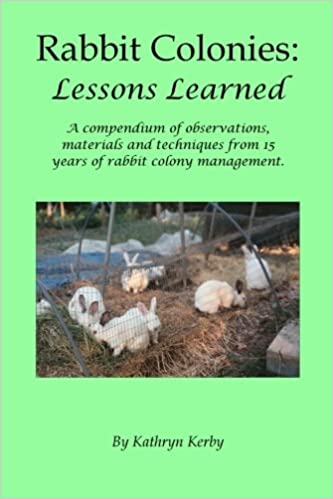

Rabbit Colonies: Lessons Learned

ANNOUNCEMENT: It's finally here! Our latest publication, Rabbit Colonies: Lessons Learned has just been released!

Are

you interested in switching over to colony housing for your rabbits?

Are you already using this method and experiencing some complications,

or want to make your approach more effective? If so, you may be

interested in a project we've been working on here. Rabbit Colonies: Lessons Learned

is an in-depth compilation of everything we've learned in the last 15

years of working with rabbit colonies. We have put this work together as

a large PDF document. It is chock-full of the issues we've faced over

the last 15 years, and detailed descriptions for how we solved them.

Here's a small sampling of what our publication covers:

- Different pen designs and the pro's and con's of each

- Dietary issues when feeding rabbits on pasture, and how to adjust their diet accordingly

- Predator problems and solutions

- Disease transmission and risks within rabbit populations, and how to address them

- Differences between adult and kit housing needs, and how to deal with them

- Breeding and kindling options, and how to avoid problems

- Weather extremes and options for weatherproofing your rabbits

- How to set up colony operations for chores efficiency

Imagine the benefits of having all this information up front, instead of facing these challenges one after another and having to reinvent the wheel! We have created this publication as if we were talking about these issues with you over the kitchen table, working through whatever ideas, challenges or goals you're working on. We know this information will provide many benefits to those who want to switch over to colony rabbit management, and those who want to make their existing operation better.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, click on our Rabbit Colonies: Lessons Learned production information page.

*You can shop with confidence with Frog Chorus Farm; we offer a money-back guarantee on all our products.*

A more natural form of rabbit herd management

Many folks have at least heard of rabbit warrens, but most have never heard of colony rabbits. Yet the two terms are very similar. Rabbit warrens are the naturally occuring rabbit social network, where multiple rabbits of both sexes and all ages will live together in a single network of tunnels and burrows. Colony rabbits are the domesticated version of that social system where rabbits are kept together in groups rather than separately. It's a system which has received precious little documentation but is growing in popularity for a variety of reasons. Let's take a look at some of those reasons, along with a few cautionary notes.

Sample Colony Rabbit Setups

Raising rabbits in colonies does not need to be complicated. The simplest form of a rabbit colony is to maintain a buck and a few does in a large group, for instance in a large pen, a converted stall, a fenced yard, etc. This small group could share a large feeder, one or two waterers, and any available shelter. On nice days that aren't too warm, they would likely bask in the sun for brief periods, groom each other, sleep in the shade, and explore their pen or yard most actively at dawn and dusk. And most importantly, they would do most of these activities together. The social nature of rabbits would have full opportunity to develop and thrive.

Multiple groups or herds can easily be maintained in adjacent cages, pens or stalls, up to whatever number of colonies the owner desires and/or can accommodate. Any animals born into any given colony, for instance as kits which are allowed to reach maturity, would weave themselves slowly into the group social structure over time. Groups of animals raised together, for instance two or three litters raised together, would generally continue to socialize peacefully even after several years of living together as adults.

Colony Population Management

If mature rabbits of both sexes are housed together, and food and wateer are readily available, that animal population is going to start growing. Most folks have heard the term "breed like rabbits", and for good reason. Rabbit populations can explode when the environmental conditions are right. If feed and water remain readily available, the population will continue to grow until the pen reaches very high densities. In other words, until the population is so high that crowding, disease, food competion and other health risks become a serious problem. If the colony was completely unregulated, yet food and water remained available, the rabbit population would eventually reach a balance point where new births would be balanced by animal mortality rates. Most of the mortalities would be young kits, although adult lifespans would drop due to the stresses of overcrowding. However, the population densities would be extremely high, and the surviving adults would often be in very poor condition.

The above situation sounds like a mess, but it could very easily be avoided in a variety of ways. First, the number of adults could be limited to a single buck and up to eight does. That ratio of one buck to eight does is generally considered to be the upper limit for an effective rabbit breeding group. Any additional does would be too many for the buck to service, and they would have multiple heat cycles without being bred.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly for a hobbyist or small farm business, the adult population could remain stable but any kits born into the group could be removed and raised separately. Those young animals would then be sold as live animals, harvested as meat animals, or form the nucleus of a new colony. For rabbit farms who are deliberately trying to expand their rabbit populations, the best individuals of each litter could be selected to form new groups while the balance of each litter was sold. This is the method we've used here, as is shown in the photo above.

A third way to control population growth would be to limit the buck's time spent with the does. Mature does will cycle roughly once every 14 days during spring, summer and fall (whenever daylight lasts 14 hours or more). If a doe is constantly attended by a resident buck, she can have up to six litters per year. At 8-10 kits per litter, that can boost the population very quickly. But if she has only restricted access to the buck, she might be bred only 1-3 times per year. This can be accomplished in a variety of ways: by rotating the bucks through different groups of does, by pulling does out of a breeding group or adding them back in, by maintaining bucks and does completely separately and only allowing breeding when desired, etc. This is where colony management would need to mesh with the rabbit owner's long term goals for that colony.

One important note when raising out rabbits for any purpose. Most of the books talk about how rabbits should be 6 months of age prior to breeding. That would imply that they are not old enough to breed until that age. The more accurate statement is that they are physiologically ready to start breeding at roughly 2.5 months of age, with a doe being physically able to kindle at only 3.5 month. Yet breeding so young can impact their growth rates and overall health. We separate out our males at 2 months of age, as in the above photo, to ensure we don't have any accidental breedings.

Adding New Animals

The situation would get a tad more complicated if additional animals are added to the group. If a second buck was introduced, the bucks could become adversaries. If the pen is large enough, the two bucks would generally stay apart from each other, but they would socialize freely with various does as all the rabbits moved around the pen. If the two bucks were vastly different in size, age or physical condition, one buck would become dominant over the other. If the bucks are approximately the same size, age and condition, they may occasionally fight. If the two bucks are raised together, for instance if they are litter mates, they will generally get along better than if they are first introduced to each other as adults. But even littermates may be prone to fighting as adults.

If an additional doe is added to the group, the dominant doe may attack the newcomer and could do considerable damage. If the does were introduced to each other slowly over time, the risk of fighting would be less. One way to do that would be to make the first introductions on neutral ground, such that the resident doe won't be territorial. After several of those introductions, the new doe could be introduced to the permanent yard. The group would still need to be monitored for instances of aggression, but the risk of serious aggression would be less.

If more than one new doe is added to the group, or if two groups are combined, the risk of some squabbling is fairly high. In that instance, the groups should be introduced on neutral ground to minimize any incidence of fighting.

Colony Rabbit Housing Options

Colony rabbit housing is surprisingly flexible. Rabbits don't need a lot of specialized housing or equipment. Let's look at what they do need.

Feeders

The type and number of feeders needed for a rabbit colony, will depend upon the number of animals and the feed/feeds they are eating. For instance, a group of young weaned littermates being fed a commercial rabbit pellet ration, may only need one or two large rabbit feeders mounted somewhere within the pen. That same group of littermates, if fed a ration of home-grown feeds, may need a hay rack, some trays for wet items such as root crops, leafy greens or other vegetables, or possibly a hanger for bunches of large leafy greens such as comfrey. That same group of littermates out in a field pen, may need very little supplemental feed if on high quality pasture. This is where a solid understanding of rabbit nutrition is critical to providing the appropriate feeder setup. Please see our Feeding Rabbits page for more information.

Waterers

The type and number of waterers is less dependent upon the details of the feeding regimen. The main determinants are the number of animals per pen, and the relative dryness of the feeds being used. The standard half-gallon water bottle which hangs on the cage side of individual cages, is perfectly suitable for up to four adult rabbits or a litter of young rabbits. Beyond four adult rabbits, the rabbits would need so much water that the bottle would have to be refilled more than once/day. In that instance, the owner can simply provide several additional water bottles, and change or refill them less frequently. Alternately, the rabbit owner could set up an auto-waterer system which requires less frequent refilling. For instance, a 5 gallon bucket with several lines to the pen, can be used to water several dozen rabbits with refills every 2-3 days. That can be a real labor-saver, except in instances of cold weather. If the water lines freeze, this setup very quickly becomes a big pain to mess with. Most commercial rabbitry operations are housed within climate-controlled buidings where the temperatures would never get cold enough for frozen lines. A small scale hobbyst rabbit owner will have to consider their particular setup, and either provide insulation, heat, and/or frequent water bottle changes during below-freezing weather.

Shelter

As we discussed on our Rabbit Hutch Plans page, rabbits do need shelter from intense sunlight, rain, snow and wind. Happily, that shelter does not need to be complicated or expensive. If the rabbits are out in a field environment, something as simple as a small raised platform, for instance a low table, can serve as rudimentary shelter against sun and precipitation. The table would preferably be low, approximately 18" to 24" from the ground (for instance a coffee table), would be low enough that windblown precipitation would not be able to get underneath. A picnic table would provide some shelter but wind-driven rain and snow could get underneath. Other shelter ideas are a low hoophouse (although the rabbits may chew on the plastic), a tarp slung over a clothesline, the underside of a shed, or even someething like a truck canopy up on blocks. Some stationary hutch designs incorporate a door which opens to a small yard. Elevated hutches can include a ramp down to the ground, and rabbits will readily learn to go up and down the ramp as needed. Many mobile field pens incorporate a hybrid design where part of the pen is open to the elements on one end, with only wire mesh as containment, and an enclosed or partially enclosed shelter on the other end made of any number of materials. This type of field pen offers good protection during spring, summer and fall conditions. A variation on this theme is to create a hoophouse or low tunnel out of wire mesh, and then lay a tarp or greeenhouse film over part of the enclosure. In either of those latter two cases, the shelter would move with the rabbit pen across the field.

One additional note on this topic, although it's not exactly shelter-related. If rabbits are out on pasture and/or have access to a field, be aware that they should not be moved onto wet ground. If they have a fixed shelter and can escape wet weather by retreating into the hutch or shelter, they can determine for themselves when the ground is too wet for their liking. Yet in mobile field pen situations, where the rabbits are compelled to go wherever the field pen is moved, the rabbit owner will need to monitor field conditions and only move the pen onto dry ground. If the rabbits need to be moved and the weather is uncooperative, the rabbit owner will either need to keep the rabbits in their current location longer than planned, or the rabbit owner will need to cover the next field location in advance, so that it's dry by the time the rabbits are scheduled to move. Under no circumstancs can rabbits be allowed to get wet or even muddy. That's a recipe for dead rabbits.

Bedding

Rabbits generally don't need a lot of bedding. They don't need any bedding at all if they are in suspended wire cages, or out in mobile field pens. And individual rabbits can be housetrained to a litter box. However, when we're talking about a group of rabbits in a single location, bedding starts to become important.

Any time a single rabbit or group of rabbits are housed on the ground, they will very quickly wear down any native vegetation until there's nothing but bare dirt. Furthermore, their presence on that patch of ground will compact the dirt such that it becomes a nearly impervious surface. At this point, urine and manure will begin to build up within the pen. Even if the urine and manure are cleaned up every day, that dirt floor is goinng to start deteriorating into a muddy mess within a few weeks (sooner in wet conditions, longer in dry conditions). That's when bedding becomes an issue.

Rabbit owners have used a variety of materials to bed down rabbits. Some of those materials are better than others. Here are a few of the most common materials and their pro's and con's:

straw or hay - these are both perfectly suitable as bedding for rabbits. They enjoy eating hay anyway, and eating free-choice hay is already highly recommended for proper gut movement and digestive function. Giving them straw would accomplish the same purpose, but they may not eat as much. If using hay, do not use alfalfa - use a clean grass hay, without any spoilage, mold, or damp spots, and try to ensure it's not dusty. Different areas of the country offer straw and/or hay at different prices, and in some cases straw may actually be more expensive. So shop around if you go this route. In either case, they only need enough hay or straw to soak up urine and keep the manure from matting down. The bedding can be reemoved periodically and added as mulch to a garden, chopped and added to the lawn in thin layers, or simply composted. If rabbit owners don't have a lawn or garden, check with neighbors who may be very happy to come get it to put on their gardens.

wood shavings - wood shavings are not as good a choice as hay or straw, but they can work OK to soak up urine. The rabbits may eat small amounts of the shavings, but usually they don't eat enough to cause any damage. However, if the rabbits are eating a lot of the shavings, they need more roughage in their diet. In that case, give them a small amount of hay each day, perhaps in a feeder or hay rack mounted on the wall, and they'll probably leave the shavings alone.

sawdust - sawdust is not a good choice for rabbit bedding, for several reasons. First, it can get into the rabbits' fur, and then they'll ingest it during grooming. Second, they may eat it anyway, and that mass of sawdust in their digestive tract can absorb moisture and become impacted, which creates a life-threatening blockage for the rabbit. Third, it's often dusty and it can create respiratory issues and/or eye discharge. One possible acceptable use for sawdust is if the rabbits have a raised hutch with a ramp to an exercise pen or yard. Sawdust could be used under the hutch if it's fenced off from their exercise area.

wood pellets - these should NOT be used for bedding for rabbits. The rabbits may eat the pellets, which then would expand in their gut and absorb a tremendous amount of water while doing so. The rabbit would a) become dehydrated and b) develop an impaction, simultaneously. That can kill a rabbit within hours.

leaf mulch - most folks don't have enough leaf mulch to consider using it as bedding. But for those folks who make a point of gathering and bundling their leaves every fall, these should not be used for bedding. The leaves have no absorption ability whatsoever. Worse, they'll mat down and create thick sheets of impervious material, making any manure and urine buildup even worse than it would have been otherwise. Leaf mulch can be used in the yard and garden in many ways, but don't use it as beddng.

fresh grass trimmings - Everything said about leaf mulch is true for grass clippings as well, with one addition. Fresh grass clippings, if allowed to mat down, will start to ferment and/or spoil. If rabbits eat that, their digestive tracts will not be happy. Avoid grass trimmings as bedding unless VERY well dried out first, in which case the clippings are essentially hay.

chipped bark and hog fuel - Chipped bark could be a decent bedding if folks can get chipped pieces very, very small. Some household-sized or small-farm-sized chipper/shredders provide a nice chip size, and in that case the material would be wonderful to use as bedding. If a commercially available chipped bark product is available at low cost, that's acceptable too. In either case, ensure that no toxic plants or trees were used in the chipping process. For instance, rhododendron is very common in some parts of the country, and it's often trimmed back by highway crews or landscapers, then chipped and sold. Yet it's very toxic. If you make your own, ensure the species being used are not toxic. If buying a chipped bark product, ask what tree/landscape species were used. If they can't tell you, don't use it. Hog fuel is a form of chipped bark, but it's chip size is much too large (roughly 2" x 4") for use as rabbit bedding.

newspaper - newspaper should not be used as bedding, for the same reasons as leaf mulch. The only time newspaper could be used is if it's shredded. See below.

shredded paper or shredded cardboard- shredded paper can be used if a rabbit owner has a huge cheap supply of it. Ensure that the shredded materials don't contain metal staples, tape residue or slippery, or the remnants of the slippery, glossy advertising inserts.

Flooring

If we just covered bedding above, why do we need to worry about colonry rabbit flooring? For the simple reason that they serve different purposes. Bedding exists to soak up waste materials. Flooring, on the other hand, is the actual hard surface that contains both the rabbits and the bedding. Some forms of flooring, such as the wire mesh in a cage, require no bedding at all. But for rabbit colonies that spend at least part of the day at ground level, some consideration of flooring is warranted.

Let's look at the different types of flooring commonly used for rabbit colonies, and compare their advantages and disadvantages:

dirt - this is by far the most common flooring for a rabbit colony, and the most similar to what rabbits would have if living in the wild. Wild rabbits will dig shallow hollows, and sometimes actual caves, if the ground is soft enough. They will trample down all the area around that spot, resulting in a worn, hard, compacted surface that doesn't absorb much in the way of water. However, they don't seem to have much regard for the surrounding terrain, and sometimes their hollows or small caves will fill with runoff water during rain events. When that happens, any kits in a nest will drown or die of chill. When domestic rabbits are kept in a small yard, they will treat the yard the same way. Any rainfall after they've been in thee yard will run off in sheets towards whatever happens to be the low spot. If that low spot is a bowl or burrow, water will pond there and turn into a mud puddle over time. If the slope is steep enough, the compacted soil will funnel all the water into a channel and erosion begins. Old written accounts of rabbit colonies in Europe describe barren hillsides with all sorts of excavations where the rabbits would rest during the day; they would come out for exercise and socialization at dusk and dawn. I should note that this is NOT the same as a warren of rabbits as is found in the UK. Those are networks of subterranean tunnels and caves which are completely underground. Domestic rabbits will sometimees tunnel into a hillside but generally not very far. If a rabbit owner has a yard area that they turn over to the rabbits, the area will slowly but surely be worn down, denuded of plant life, and remade into a dirt drylot. Or a mudlot in the wet season. Additionally, any digging near a fenceline will very easily give the rabbits access to areas beyond the fence. For these reasons, dirt is not really recommended as a permanent flooring for colony rabbits.

growing pasture - Pastured rabbits housed together in colonies is a potent, sometimes profitable combination. But it has to be done carefully. Maintaining one or more rabbit colonies on pasture requires that the colonies not only be moved regularly, but that the pasture be dry. Furthermore, the pens holding the rabbits must be escape-proof, particularly where predators are likely to pick off any escapees. And finally, the nutritional value of the pasture should be folded into the ongoing feeding program for the colony, such that they are making the best use of available forage, while ensuring that all their nutritional needs are met. With all those variables, colonies on pasture can be a challenge. Yet it can definitely be done. For more information on how to maintain rabbit colonies well on pasture, please see our Feeding Rabbits, Rabbit Hutch Plans and Rabbits On Pasture pages.

wood planks or sheets - This is not a common option when building a new pen or shelter for rabbits, but it is very common when retro-fitting an existing stall, shed or other structure for use with colony rabbits. It can be done well, but with some strong limitations. The major advantage is that the rabbits are up off the ground, and thus out of the mud during wet weather. Wood is also strong enough that it will resist their digging behavior, for awhile. Heavy planking as is found in some old barns would take years of abuse before showing serious damage. However, the OSB and/or plywood commonly used in new sheds is much, much thinner and would show damage after less than a year of continuous use. The two strong disadvantages would be that wood of any kind will allow urine to soak in if that urine is allowed to stand for any length of time. Even sealed wood will eventually lose it's protective coating and allow urine to penetrate. Secondly, by its very nature the wood flooring would prevent grazing. If the wood flooring is in a secure shelter area which the rabbits use in conjunction with a grazing area, then this is no problem. If rabbits are housed in this pen 24/7, they would benefit greatly from having browse, hay, or other green fodder brought to them at least a few times a week.

concrete - like wood, concrete is most common when converting a building from some other use, over to colony rabbits. The single most common occurrence of concrete is when a rabbit colony is set up within a garage or basement. Concrete has some surprising advantages. First, it's virtually impervious to rabbit digging activity. Second, it can easily be sealed so that it's also impervious to urine. Third, even without sealing it's a breeze to clean up. The main disadvantages are the cost, and the obvious fact that it isn't very portable. When converting an existing building over, the cost may not be an issue. And if the rabbits have access to an outside yard, or to browse grown inside and/or carried to them, the portability may not be an issue either.

linoleum, vinyl or other manmade flexible flooring - These options also occur most frequently when some existing structure is being converted over to colony rabbit use. Perhaps surprisingly, all of these flooring types have the same advantages and disadvantages as concrete, and can be used very successfully. The one major exception is that if a single tiny little tear or seam develops, the rabbits will quickly start to chew on and paw at that tear or seam, until they've started to shred the flooring. Additionally, they will ingest some tiny ribbons of material as they chew. So these types of flooring must be very well sealed, and inspected regularly to ensure no such edges occur.

masonry tile - as with concrete, this type of flooring is almost unheard of for new rabbit shelter construction. But existing structures being converted over to rabbit use, may feature this type of flooring. This type of flooring has most of the same advantages and disadvantages as concrete, with two additions. First, the tiles themselves may be rather slippery, making it difficult for the rabbits to get traction. Rabbits don't generally walk, trot or run like other animals, so this isn't a huge issue. However, they would still appreciate some form of stiff bedding which would give them something to push against when they try to hop. Secondly, the tile is generally impervious to any damage but the grout between tiles is surprisingly vulnerable to staining and moisture damage. Enough damage and the tiles can lift away from the backing, or even break if water gets under a tile then freezes. Grout can be sealed with some degree of success, but it's a hassle and sometimes the sealant doesn't "take". And once that grout is stained or damaged, it's expensive to fix if it can be fixed at all. If converting over a tiled floor for use with colony rabbits, consider sealing the whole thing or laying down some kind of secondary floor to ensure the tile floor isn't damaged.

Rabbit Handling for Colony Rabbits

Many of the well-established texts on rabbit management, either imply or state outright that rabbits cannot be kept together because of increased disease issues. While that is an outdated philosophy, the rabbit owner should be aware of some caveats and best practices to minimize communicable disease, and to ensure any individual rabbit can be captured for inspection and/or treatment.

First, handling the rabbits on a frequent basis can really help when it comes to catching them for examination and/or treatment. If a rabbit owner has only six rabbits, that can be a pleasant task. If a rabbit owner has a commercial herd of dozens or hundreds, that isn't so easy. Any amount of calm, quiet handling will help, even if it's only once or twice a year. The more calm handling, the easier each handling session will be.

Second, it is helpful to train them to come to treats in the hand. Rabbits like snacks as much as anyone, and they can (and do) develop particular fondness for this-or-that special treat. That can be a training aid to teach them to come to us, rather than us having to chase them down. And remember, rabbits have developed their evasion techniques over hundreds of thousands of years. They're very, very good at not being captured if they feel threatened. How much easier life gets, when they come to us rather than us having to go after them.

Third, it's very helpful to have a pen, cage or shelter which can be divided up into quadrants or smaller compartments. This helps to minimize the amount of space in which the target rabbit can run to escape capture. Even when they are accustomed to being handled, and/or willing to come for treats, sometimes an excited rabbit will simply run. Trying to capture a single rabbit in a single 12' x 12' stall very quickly becomes an exercise in profound frustrations as the rabbits run in circles around you. Even smaller pens, like our first 4' x 10' field pens, can be maddenly large when trying to capture a rabbit through a hatch. Regardless of pen size, any kind of dividers or partitions will help corral the rabbits into smaller and smaller spaces until they are within easy reach.

Fourth, having something akin to a bird net or fish net on a long handle, can help capture rabbits as long as the pen isn't very big. Rabbits at liberty in a yard 50' x 50' will be impossible to capture even with a net because they simply run away beyond reach.

A combination of partitions to reduce the area, and a net of some kind to easily capture them, and familiarity with being handled, can go a long way towards making individual examinations and treatments a whole lot easier. Which brings us to health exams.

Colony Rabbit Health Care

Rabbits are not only masters of escape; they are also masters of hiding their health issues. If you were on everyone' menu, you'd be a master of hiding weaknesses too.

Rabbits in any management system are subject to a variety of health issues. Unfortunately, they can hide all sorts of issues, from weight loss to dental problems to sore hocks to mastitis, because they'll simply sit there and do their normal thing. It's not until we handle them that we realize uh-oh, something is very much wrong. If we wait until they go off their feed, by then it's often too late to do anything to help them.

Some rabbit owners, particularly of large commercial herds, simply don't have the time or personnel to physically check every rabbit on a frequent basis. Pet owners, on the other hand, might handle their rabbits every day. Each owner will have to decide how much handling time is practical. Regardless of that answer, some basic quarterly health checks are warranted:

Check and record body scoring and condition: body score, also known as lumbar score, has become the preferred method for quantifying and describing an animal's overall health and condition. This scoring system uses either visual or in-hand assessment to determine how much muscle and fat is on the skeletal frame. Common points of examination are over the ribs, along the lower spine (thus the term lumbar score), and through the loin area. A scale of either 1-5 or 1-10 to describe how much fat and muscle an animal's frame is carrying in those locations. A score of 1 is emaciation; while a score of 5 or 10 is extreme obesity. The middle of the range, whether the range is 1-5 or 1-10, is considered ideal. So for instance, a rabbit with a lumbar score of 3 on the scale of 1-5, would have a nice amount of muscle alongside the spine such that the spine itself could only barely be felt. The hips wouldn't feel bony, the ribs would have some fat on them, but the loin would have a "waist". An obese rabbit would score either a 5 or 10, ie, the highest end of whichever scale is used. The rabbit's body would have layers of fat such that the skeleton couldn't be felt even with pressure, and the rabbit would be uniformly thick through the loin, or even have something of a belly such that the loin area would be larger in diameter than the heart girth. an emaciated rabbit, on the other hand, would probably look OK but would feel very bony. The spine wouldn't have a lot of muscle on either side, the hips would feel bony, the ribs would feel obvious beneath the fur, and the loin area would be noticeably smaller in diameter than the heart girth. One of the simplest health checks we can do on a quarterly basis, is to handle each rabbit, give it a body condition score, and record that score on the animal's feed card or health files.

Teeth - rabbits have teeth that grow throughout their lives. Their incisors or something akin to rodent teeth in that they need to gnaw constantly in order to keep them worn down. And like beavers, rabbits can go through an amazing amount of fiber in the process of keeping those teeth trim. At least each quarter, ideally while doing the body condition scoring, the rabbit's mouth should be visually checked to ensure that the incisors meet up nicely and evenly, and none of those teeth are broken off or growing longer than the others. If one is broken off, monitor it to ensure it grows out and mates up with the others around it. If one is longer than the others or misshapen, it can be filed down or trimmed (by a veterinarian) such that the rabbit's chewing is normal again. If a rabbit seems in good health but has gone off feed, the first thing to check is the teeth.

Weight - a mature rabbit's weight should be relatively stable. I won't list typical weights here because different breeds have vastly different average weights. Simply recording the rabbit's weight quarterly will help show if that rabbit is getting too much or too little feed. Comparing the amount of feed to the weight, will help an owner distinguish between thrifty animals and hard keepers.

Disease Issues

As stated above, many of the older books dismiss colony rabbits out of hand because of perceived health issues and/or risk of disease. There is some truth to that statement, but as with many other things in life it is a risk which can be minimized. And that risk certainly doesn't cancel out all the other benefits of housing rabbits together in natural social groups. Let's take a look at some disease issues and how they can be minimized or managed.

Communicable Diseases - rabbits, like any other species, are subject to a whole range of viral, bacterial, fungal and parasitic diseases. I won't bother listing them all here; most rabbit books and countless online sources of info already exist on that topic. Not all rabbits will have the same vulnerability to any given disease, regardless of how they are housed. Some individuals seem to have a constitution of iron, while others get sick at the drop of a hat. This is natural and normal for an group of animals. Many folks believe that their only job as owners is to build/maintain the housing, keep the animals fed and watered, and harvest whatever products the animals produce. I say that's just the start. In fact, I think that's the easy part. Identifying which disease(s) are most prevalent in our areas, finding ways to minimize their buildup, identifying naturally resistant rabbit bloodlines, then boosting our entire herd's health, is the mark of a truly professional livestock owner and manager. It often makes the difference between a livestock operation that just barely gets by, versus one which truly thrives. So rather than focusing on all the possible diseases, I would encourage owners to focus on making their animals as healthy as possible, through clean housing, high quality nutrition, species-appropriate social groups, and moderate production goals. By focusing on these issues, the vast majority of communicable diseases won't ever be an issue. These measures will also help identify and control the few disease issues that surface now and then.

Nutritional Diseases - Frankly, I believe this to be the much greater health risk to most domestic rabbit populations than any communicable disease ever would be. Simply opening a bag of rabbit pellets and pouring the pellets into a feeder, is woefully insufficient to creating and maintaining a vibrantly healthy rabbit herd. Rather than repeat all the relevant information here, I'd encourage folks to go read all the information on our Feeding Rabbits page for a good overview of how to feed rabbits not only to keep them alive, but to help them thrive. That page doesn't focus on colony rabbits alone, but everything there applies to colony rabbit nutritional management.

Environmental Diseases - This category includes things like rabbits becoming sick after being exposed to wet conditions, muddy conditions, extreme heat, harsh winds, and/or the stresses of predator activity. Some people would use this category as a reason to not raise rabbits in either a colony and/or pastured setting, due to fears that they'll get sick from living in such rough conditions. Hardly! Their cousins in solitary cages within closed-up buildings also have their share of environmental diseases - sore hocks from living on wire, behavioral aberrations from lack of social contact, digestive issues from 100% pellet diet, respiratory issues from ammonia buildup, etc. Any herd management method, indoors or out, can be done well such that these problems are avoided. Conversely, any management method, indoors or out, can exacerbate environmental issues until they become full-blown health crises for the entire herd. Careful attention to proper housing can make the difference. Using information on this page, our Rabbits On Pasture page, and our Rabbit Hutch Plans page, an owner can relatively easily minimize environmental health issues.

Social Competition, Bullying and Fighting - when most folks think of rabbit health issues, these types of threats rarely come to mind. They're not even on the radar for herd owners who manage rabbits in individual cages. But for rabbits housed together, either in pasture pens or some kind of colony setup, various social stressors can be just as big an issue as any virus. To start with, rabbit groups definitely have a pecking order which is enforced amongst and between the sexes. For instance, each rabbit group will have a dominant doe, several in-between does and a doe at the bottom. If that group also includes males, the dominant male may defend whichever doe he favors, and that favoritism can come and go over time. Conversely, animals of either species can sometimes create rivalries or enemies, such that a single pair of animals will be prone to fighting, or a single dominant animal will always go after a certain lower-ranking individual. Ironically, it can also occur that a lower-ranking individual will constantly pester a higher-ranking individual, if the difference between their two ranks is very small. And at the far end of the scale, fights can break out between two individuals. Why does any of this matter to the rabbit owner? Because any animal that is being bullied or heckled by another, is going to eat less, sleep less, drink less, and in general be less healthy as a result of all that interference. The damage from actual physical fights can be patched up and monitored for healing, but the damage from social pressures is harder to detect. Any time rabbits are housed together, these social relationships need to be at least recognized. If an individual is doing poorly in one pen, sometimes merely moving that individual to another pen will solve the issue. Or if an individual is bullying everyone else, removing that individual to another older pen, or culling them entirely, may restore peace. Each owner should at least keep tabs on basic social harmonies within any rabbit group, and be ready to move animals in or out as needed to help minimize the worst of these issues.

Colony Housing

I have deliberately resisted providing specific guidelines for housing, simply because so many options are equally suitable. Yet some guidelines are helpful. Adult rabbits of average size need a minimum of three square feet of floor space per animal, but four to six square feet is better. So a group pen would need to be large enough to provide that much space per rabbit. A field pen would need to provide this much floor space, AND be moved often enough to provide fresh grazing.

Some very common colony housing setups have included:

- a converted horse stall, with or without an outdoor run

- a small shed (with or without access to the outdoors)

- a chicken tractor either with an added floor, or moved across field fence laying on the ground

- a small hoophouse or greenhouse, either portable or stationary

- a garage or portions of a garage

- a small geodesic dome, either portable or stationary

I could recommend any of the above, but they can all be perfectly suitable forms of housing for a colony. The individual rabbit owner will ultimately need to decide which form(s) of housing are most appropriate, based on the available facilities, rabbit population, weather, production goals and costs. In general, though, any form of housing which provides an easily-cleaned environment, well lit and airy, with access to the outside and protection from weather/predators, will be perfectly suitable.

Nesting areas and kindling behaviors in colony settings

A nestbox for an average sized doe is approximately 9" x 18", and she needs room to get into it and jump out of it. It can be either on ground level or slightly above/below. Most of all, it will need to be in some quiet location where other rabbits won't bother it, and it'll need to be protected from wind, rain, snow, cold weather (anything below 40F can start to cause chilling) and predators. Mother rabbits do not stay with their nests all day. They nurse once/day and they may check on the nest several times during the day, but the mothers will readily leave the nest to go eat, sleep, groom and socialize. So if colony does are going to be kept within the colony while producing litters, the group pen will need to provide one or more areas for these nests. Some rabbit owners simply pull the pregnant does out of the colony to kindle in a separate cage in a more secluded and/or protected area. Other owners provide a variety of nesting boxes in various locations and let the doe(s) choose whichever nest box they prefer. Be advised, however, that rabbits can and will kindle out in the open if they don't find a nesting area that they like. In that situation, the kits will often die either from exposure or from being attacked by the other rabbits.

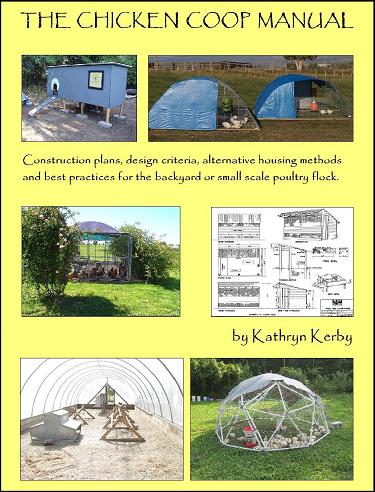

Our Successful Farming and Ranching Books

We released our very first self-published book. The Chicken Coop Manual in 2014. It is a full color guide to conventional and alternative poultry housing options, including 8 conventional stud construction plans, 12 alternative housing methods, and almost 20 different design features. This book is available on Amazon.com and as a PDF download. Please visit The Chicken Coop Manual page for more information.

Rabbit Colonies: Lessons Learned

We started with rabbits in 2002, and we've been experimenting with colony management ever since. Fast forward to 2017, when I decided to write another book, this time about colony management. The book is chock-full of practical information, and is available from both Amazon and as a PDF download. Please visit the Rabbit Colonies page for more information.

The Pastured Pig Handbook

We are currently working on our next self-published book: The Pastured Pig Handbook. This particular book addresses a profitable, popular and successful hog management approach which sadly is not yet well documented. Our handbook, will cover all the various issues involved with pastured hog management, including case studies of numerous current pastured pig operations. If you have any questions about this book, please Contact Us.