For The Love Of A Cow

January 5, 2011

Most days on the farm pass, one like another, until they all blur into what is hopefully a pleasant patchwork of memories. Collecting eggs, counting piglets, transplanting tomatoes, harvesting corn, are all tasks that need doing but they don't stand out as being particularly memorable. The days progress and the seasons progress and you wonder where it all goes.

Then there are days when something so unusual or scary or potentially life-changing occured, that they stay crystal clear in our minds for the rest of time. Today was one of those.

On a normal winter day I get up well before dawn, open the gate as the husband drives off to work, do a cursory check of the livestock, then go start the woodstove and otherwise get the morning going inside. Then I do chores a few hours later after the sun has come up. If I have animals that are recovering from an illness, due to give birth, or otherwise under observation, I will use this time to check on them. But 99% of the time, the farm is still quiet. Given that it's January, most of our outdoor activities are put away for the winter, so morning chores are relatively simple. No need to get started super early. And today started out about the same. The weather was starting to turn warmer so the temperature was much milder than it had been. No rain, wind or snow overnight so nothing to check in terms of fence damage or roof damage. I glanced into each of the livestock shelter areas, and was pleased to see that everything was quiet. At which point I went back inside to heat up the house, get some breakfast going and let the sun come up.

When I came back outside two hours later, something was very different. One of the cows was moaning. I usually feed them first so I was already headed down to that barn. At first it sounded like a normal "feed me!" bawl. But well before I got there I could not only hear something wrong, I could see it. One of our cows, for reasons that still escape me, decided in the pre-dawn light that she was going to try to jump over a stall divider. At which point she promptly got stuck. Our stalls in that barn are formed by tall, rugged metal corral panels: heavy-gauge tubular steel rails welded together into panels 6' tall and 10' long. They are, as far as I know, darn near bombproof. And at that point, I also realized they were apparently cow-proof, because our cow Gracie was high-centered over the top of one of them. The bedding pack had already built up about 24" at the base of the panel, so instead of 6' high it was functionally only 4' high, which is roughly level with her topline. Normally a cow won't try to jump something so tall. Yet, she decided she could jump it. How she got her front feet over that top rail I'll never know. But when I found her she could either touch ground with her front feet, or with her back, but not both. She was well and truly stuck.

When you see something like that, something so outside your normal expected reality, it takes a moment for the situation to really sink in. It suddenly dawned on me as I stood there that she would need help to get down. How do you lift a 1500 pound cow off the top of a corral panel and back to the safety of level ground? Then I realized something else. Despite what had to be a very uncomfortable position, where her own weight was compressing her heart and lungs such that I could hear her breathing several feet away, she wasn't panicking. Yet. She was looking at me asking for help, but she wasn't thrashing around. So in the naivete that we humans sometimes feel when faced with insurmountable odds, I tried to pick up my cow. Just the front end, mind you. I wasn't that far gone. I thought if perhaps I could just shift her weight back a little, she could finally reach the ground with those back feet. But physics shows no favoritism, not even when we have the very best intentions, and 130lbs versus 1500lbs was going exactly nowhere. Then I thought if perhaps I could put some hay bales under her, she could stand on those either in front or behind. I told her to please not worry, I would be right back, but I was going to get some hay bales to help her. Her pleading eyes told me to hurry.

Four bales later, and we had made no progress. I realized I needed some help. First I called my husband who was 45 minutes away. Only got his voicemail. Infuriating that some mundane task would have him away from his phone at that precise moment. Next I called the vet clinic that was only 5 miles down the road. They do large animals and surely they had some big beefy interns that could come up and help me out. Well, it turns out they had a slender young lady vet who could come up and help me out, and she'd be there as soon as she could. I told Gracie that help was on the way. With the hay bales I had been able to help her lift herself a little off the top rail so she was breathing easier, but every five minutes or so she'd start struggling again to get over the rail. I prayed that she wouldn't get into serious trouble before I had some help.

The vet finally arrived after what seemed forever, and we concluded that yes the hay bales really were the only way to go, since we couldn't realistically lift her any other way. We also concluded that because of her positioning and the fixed nature of the panel, the only way off the top of the panel was to continue forward into the next stall. Which already had an occupant - our other cow. So far I'd kept that other cow distracted and busy with her morning hay. But she was getting more and more curious about all the fuss behind her. Each cow stall is only 10'x15', which didn't leave a lot of room for one full-sized dairy cow, the two of us, and the front half of another dairy cow. At some point, the second cow's curiosity and friendliness was going to become a problem.

While Gracie rested precariously balanced on her perch and some hay bales, we quickly brought in another corral panel to divide the stall in half, such that we had room to work and our second cow Hope would be relegated to watch from the sidelines. She didn't much care for that but she quieted down soon enough and went back to her hay. But by this time, roughly 2 hours had come and gone since I'd found Gracie. It was probably 3 hours since she'd gotten stuck. She was starting to get tired, and I think scared, and her breathing was becoming somewhat ragged. We needed to do something and we needed to do it soon. The vet nearly emptied our hay shed to create more cushion and elevation under Gracie's feet, while I called my husband again. Happily he answered this time. My message was simple: "Come Home Now. We Need You." He was on his way.

The next 45 minutes passed as the previous 2 hours had already passed, with Gracie struggling periodically to free herself while we tried to position bales under her front and hind feet so she could get better purchase. The hope was that as we steadily built up the hay around the corral panel, at some point she'd be able to stand and somehow move off the rail. But our working conditions were tight, she faced an increasingly steep descent, which cows don't like, and worst of all, she was tiring quickly. We had built up the hay under her front legs, to help lift her off the rail so she could breathe easier. But that shifted a lot of her considerable weight back to her hind legs which were never designed to carry that load. We could see the muscles in her back legs starting to tremble, and she was shifting from one leg to the other as she got tired. She was also making efforts to change position less frequently. We feared she was starting to give up. Finally, I heard my husband's truck pull up. More help had arrived.

He could see the situation clearly enough as he walked up; it didn't take much discussion for him to head back to the house and change into farm clothes, then hustle back out to us. By this time we had actually made a bit more progress, simply by rocking Gracie forward such that she was now kneeling on bales on front and most of her body had passed over the smooth top rail. The fact that she had not yet suffered any broken skin (or broken bones for that matter) was a minor miracle. But the real challenge was clearly before us. The rail was now directly under her loin, that narrowest spot right before the hip. Somehow we had to lift both hind legs up and over that top rail without either of them getting caught in the rails beneath. If we could get those feet up and over, we were home free. If one or both of them got hung up as the mass of her weight began to shift forward and down, we would have nightmarish injuries very quickly. She was still cooperating with us and her breathing was a lot easier now that the pressure was off her heart girth. But would she cooperate with us enough to lift up her entire hind quarters, reposition both back feet, and deliberately slide her to the ground? The moment of truth was upon us.

As we were getting ready to make that last shift, she decided for us that she was going to change the plan. Looking back, I think that decision probably saved the whole situation. Some would question whether she actually decided, or it was just dumb luck, or random chance. But at that moment when we were preparing to make our big coordinated effort, she simultaneously rolled to the left, lifted her right hind leg enough that her knee cleared the rail, then rolled back to the right so that she was now laying on that haunch. Not by much, but it was enough. With her now laying partially on her side, and her right rear leg almost over the rail, she also presented us with an unimaginable gift - her left rear leg was free and clear. In that moment she had done everything she could do to free herself, and she was holding position as best she could; it was up to us to do the rest.

Anyone who has ever been in a truly frightening situation is aware of something called time dilation. It's where you are so hyper-aware of what's going on, that every second seems to take several minutes to unfold. You see things moving, you see what needs to happen, you recognize risks and you make choices about how to proceed. In the moment that she rolled back over onto her right hip, we had just a few seconds to work with, and we couldn't stand around and talk about what to do next. Somehow, we all knew what needed to happen without speaking, and we all just did our part. The vet shoved hard against Gracie's back to ensure she didn't simply slide into the back wall. My husband shoved Gracie's rump straight forward with all the energy his 6'2" muscular frame could manage. And I, despite every ounce of good sense I'd ever learned working around large animals, grabbed both her back feet, then tugged and restrained and guided them simultaneously and safely over the top rail. As the majority of her body shifted beyond the rail and down towards the ramp of hay bales, gravity took over and she slid down to the stall floor, just as pretty as you please. If we had had a year to train for that event, we couldn't have pulled it off any smoother than it went. And suddenly, it was over. She was safely on the floor of the stall, breathing hard, while the rest of us stood there suddenly realizing we were panting as well.

The next 15 minutes were spent recovering, for all of us. Gracie just rested on the floor, while I monitored her breathing to ensure she was able to get enough air despite the fact that her rumen now rested directly on her lungs. She closed her eyes for awhile and seemed to just relish being on terra firma again. The vet prepared some drugs to help her body deal with the aftermath of being caught for several hours. My husband started to clear away the hay bales and ensure we had a safe work area in case she started to struggle to her feet in the enclosed area and we had to move out of her way quickly. But she was in no hurry to move. She laid resting on the floor of the stall for 15 minutes or so, then tucked up all four legs so she could roll back over and rest in a more normal position, with hooves underneath her. When the big needles came out and the injections started, she decided nope, she's had enough and got up as if it had been a perfectly normal morning. A few moments later, she started looking around for some breakfast. Total elapsed time, about four hours.

A friend of mine once admitted to me that he worried about our efforts to get our farm going. "You care too much," he explained, "you can't get so attached to those animals if you're going to try to run that place like a business." I strongly disagreed with him then, and I still do. Anyone who has ever been in business for themselves understands that they have to love what they do. Otherwise the long hours, the startup bills, the learning curve, the competition just isn't worth it. That applies to farming as well. You'd better love what you do most of the time, because it's hard work even when you're making good money. But I'd go further and say that any sort of job that deals with living things - whether it be medicine, botany, child care, farming, etc - the caretaker must somehow love the creatures that come with the job. Or that person is in the wrong job. When we bring living things into our lives because we want to work with them in some capacity, I believe that automatically obligates us to also adopt certain responsibilities for their comfort, their welfare, their physical and mental health. And yes, their happiness. If we don't love to work with those creatures, we do them and ourselves a disservice. They don't have the option to quit the job, so it's up to us to choose our jobs wisely. At which point love and respect for the animals is not merely a desireable characteristic. It's a requirement.

But there's another dimension of that choice. When we devote ourselves to learning how best to care for them, handle them, feed them and train them, we are often rewarded with such trust and respect in return that we are given a chance to really work as partners. All through Gracie's ordeal today, she never once lost her temper, or got frantic, or lashed out at any of us trying to help her. Yet being hung up on that rail had to be extremely uncomfortable, borderline excruciating. I can't count how many times I was in a position that if she had lashed out, I would have been injured or killed by those hooves. But she didn't. There is no doubt in my mind that she knew we were trying to help. Furthermore, once we had come up with a game plan, she seemed to understand what we were trying to do and then suddenly we were all working together on the same plan. We did absolutely nothing to cue her to roll over on her side. Even if I'd known in advance she was going to get hung up, I never would have thought to train her to do that. But she could feel in her own body that she had to position herself that way, or our plan would never work. And so she chose the right time, when we were in the right place, and she rolled. She did her part and we did ours, and we got her down. Simply explaining that chain of events as random chance would be to ignore all the previous context of what had happened. She knew the deal. It was only due to her cooperation that we were able to get her down without so much as a grazed knuckle.

Of course my schedule was blown for the day, so after we were sure she was OK I hustled off to the rest of the farm to catch up on all the other morning chores. Then I realized that the adrenaline had worn off and I was feeling shaky. I got inside to eat something, then laid down and took a bit of a nap. When I got up I went out to check on her. She'd had a full breakfast by then, and a nice long drink, and time to ruminate on the morning's events. Normally she's a reasonably friendly cow, not prone to getting in your face but enjoying a scratch once in awhile. But this afternoon when I checked on her, she did something she'd never done before. She extended her neck way out over the stall door and into the aisle, and sort of wrapped her head and neck around me. She stood there like that for a few moments, while I talked quietly to her about how proud I was of her and how brave she'd been, and how cooperative. I wasn't sure if she wanted to give, or recieve, reassurance. Maybe both. I know I felt better after getting that "hug" from her. I hope she felt better too.

Cows are called "the nursemaids of humanity" because so many cultures have relied on them to provide such nutritious foods throughout history. I had heard that phrase repeatedly over the years but I had never really understood it until today. Whatever friskiness she may have felt this morning to inspire her to get into trouble, had very quickly yielded to some kind of combined instinct and intuition and understanding that Cow and Human need to work together to get things done. If either of us had forced the issue, one of us would not have walked out of that stall in one piece. It really was that simple. But by working together, we both came out in good shape. There's another farming phrase which goes "those who stir the soil are eventually stirred by the soil." I found myself wondering tonight, upon reflecting on the day's events, if perhaps there is a bovine corollary to that phrase. If so, perhaps it would go "those who care for the cow, are eventually cared for by the cow." I guess time will tell if that's accurate. But tonight, I sure love that goofy red cow.

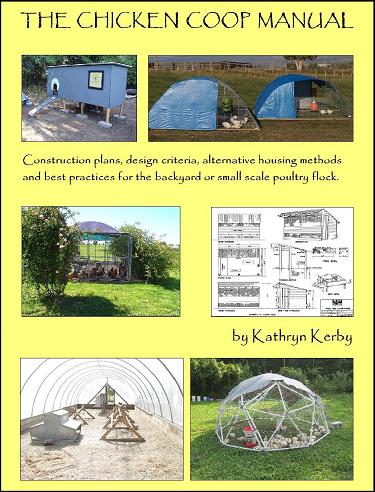

Our Successful Farming and Ranching Books

We released our very first self-published book. The Chicken Coop Manual in 2014. It is a full color guide to conventional and alternative poultry housing options, including 8 conventional stud construction plans, 12 alternative housing methods, and almost 20 different design features. This book is available on Amazon.com and as a PDF download. Please visit The Chicken Coop Manual page for more information.

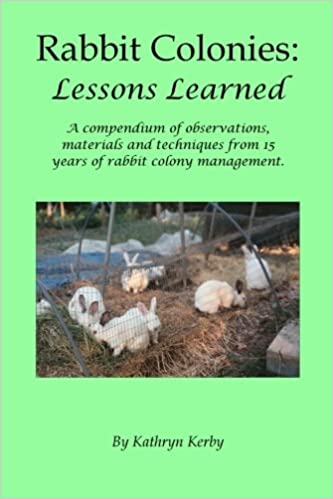

Rabbit Colonies: Lessons Learned

We started with rabbits in 2002, and we've been experimenting with colony management ever since. Fast forward to 2017, when I decided to write another book, this time about colony management. The book is chock-full of practical information, and is available from both Amazon and as a PDF download. Please visit the Rabbit Colonies page for more information.

The Pastured Pig Handbook

We are currently working on our next self-published book: The Pastured Pig Handbook. This particular book addresses a profitable, popular and successful hog management approach which sadly is not yet well documented. Our handbook, will cover all the various issues involved with pastured hog management, including case studies of numerous current pastured pig operations. If you have any questions about this book, please Contact Us.

Weblog Archives

We published a farm blog between January 2011 and April 2012. We reluctantly ceased writing them due to time constraints, and we hope to begin writing them again someday. In the meantime, we offer a Weblog Archive so that readers can access past blog articles at any time.

If and when we return to writing blogs, we'll post that news here. Until then, happy reading!