|

Search this site for keywords or topics..... | ||

Custom Search

| ||

New Life For Old Equipment, Part I

April 28, 2012

A side delivery rake, circa about 1940's, built to be pulled by either a team of horses or one of the tractors which were just becoming common in those years. We opted for this type of rake because they are lightweight, efficient, adjustable, and easy to maintain. Finding a rake like this in good condition took some research, some patience, and some negotiating. With decent care, it should continue to provide good service for decades to come.

Ever since last year’s hay harvesting fiasco, we’ve been mulling how to do a better job of things this year. And as most things go with farming, any hope of a good harvest requires a lot of prep work well in advance. In the context of hay, that prep work began the moment we realized that we needed efficient ways to cut, and turn, and bale up the harvest. Our scythe last year did cut the hay, to be sure. With practice we could have cut the hay via scythe as quickly as via other methods. But we didn’t have any way to quickly turn the hay, nor did we have transportation for loose hay. We needed conventional bales to make the most of our hay field, and feed our animals cost-effectively through winter. Add to that our region’s notoriously short hay harvest window: July and August are the only two months we can reliably have enough warm, dry weather to make good quality hay. If we really truly wanted to put up our own hay, we needed different equipment.

The acquisition of our tractor in December 2011 was the first big step in that direction. I had held out hopes for a long time that I could get our horses trained up to do haymaking work. But with the loss of our Gaye over the winter, that plan had to take a back seat for the time being. We did have the tractor as a power source, so our next goal was finding the three basic implements for haymaking: a mower, a rake and a baler.

As simple as that sounds, the details were a lot more involved. The first order of business was making sure that any implement we purchased would be large enough to realistically harvest 10-20 acres of hay in a timely way, say in 5 acre batches. While making 5 acres of hay with a hand-held scythe is a challenge, that acreage is well within the range of all commonly-available tractor-drawn haymaking implements. Ironically, the equipment needed to also be small enough that our small tractor (and our small budget) could handle them. Here is where things got a little trickier. Our little tractor Dorothy is a Ford 9N, which is one of the earliest and smallest common makes of tractor in the USA. She’s only got about 22hp to work with. Her size and hp rating limited our implement choices. She would have plenty of size/power for most traditional sickle bar mowers, but she was too small for the newer flail and drum-type mowers. Rakes usually don’t require much power, particularly if they are ground-driven. In that instance, the tractor merely needs to pull them across the ground, and their own wheels are geared to a transmission which turns the rake itself. There, the main issue would be the weight, width and cost. Many modern rakes are lightweight wonders of engineering, but their cost was relatively high. Yet our area has a relatively good supply of older types, still in good working condition. These older models were typically very light weight, low cost, and efficient. That gave us something specific to look for, for two of our three needed implements.

I knew from my initial online research that sickle bar mowers would be easy enough to find either used or new; the trick would be to find models which were in good shape without being too expensive. And we knew what type of rake we wanted - the original side-delivery rake, as illustrated above. After watching the used farm equipment ads for awhile, and not finding any good candidates, I decided to run a Wanted ad which listed what we were looking for. Happily, I had several replies. Some of those ads sounded like a good deal but didn’t pan out for a variety of reasons - too far away, too expensive, too much repair work required, etc. But one ad sounded promising - he had both a rake and a mower of the types we were interested in. The rake was in good shape and was field-ready but for a few bent tines. The mower needed quite a bit of work, but had been put away in working order and probably just needed a cleaning, a sharpening and a lube job. We drove down to look at them, and found exactly what he had described. The rake was in great shape, while the mower definitely needed to be serviced. It didn’t have any broken or missing parts, but the knives definitely needed to be sharpened, the gear box was dry, and the whole thing had been sitting awhile. We negotiated a price for the rake, and he offered to toss in the mower for free simply to take it off his hands and out of his yard. Free is a pretty darn good price, so we took both.

After we had negotiated the terms of the purchase, the seller told us how he'd ended up with the rake. His property was part of an old dairy farm, and this rake had been on that dairy farm for decades. When the dairy farm was eventually sold and broken up into suburban parcels, the new owners didn't have any use for a hay rake, and were considering sending it to the scrap pile. The seller bought it simply because it was, in his opinion, a beautiful piece of American agricultural history. He never used it himself, but he couldn't bear the thought that it was going to be scrapped simply for the sin of having outlived its original owner. He was delighted to learn that we intended to actually put it back into service. If we take good care of it, and the rest of our equipment, they may outlive us as well. Somehow I find that a very satisfying thought, particularly in this day and age of disposable products and planned obsolescence.

We had two of our three haymaking implements. The third piece, the baler, has proven to be more challenging to find, for a variety of reasons. We may have tracked down a model which will work for us. But until we finalize that deal, I’ll save that story for a little later. In the meantime, suffice to say that we’re thrilled to have gotten even this far. Many well-respected growers in our area warned us that we’d have to spend upwards of $20,000 for a decent set of haymaking equipment, including the tractor. To date, we’ve spent only a fraction of that amount - $800 for the tractor purchase, another $400 for various repairs (including our tutelage under our mechanic’s watchful eye), $250 for the rake and mower, and another $250 to have those implements trucked from their previous owner to us. We estimate we’ll need to put another $500 worth of parts and repairs into the rake and mower, with the bulk of that cost going to the mower. Still, we’ve spent $1700 so far, and we’ll probably spend $2200 total on the equipment we have so far. The baler will probably cost another $2000, between purchase and repair/tuneup expenses. So we’ll be into haymaking this year for less than $5000. That’s a much easier figure to budget than the $20,000 we were warned of. It just goes to show that careful shopping, careful evaluation, and learning to do our own work as often as possible, can definitely add up to significant savings. But stay tuned, Dear Reader, as the story about the baler unfolds. In the category of rescued old equipment, that baler’s tale is shaping up to be a rather amazing story in and of itself.

Submitting the Organic Certification Paperwork

April 21, 2012

The paperwork I’ve put together for our organic certification is plentiful enough, that I’ve set up a series of notebooks, each with various dividers, to keep everything organized. These records eventually will cover years’ worth of production. One of the biggest complaints about the organic program is the documentation requirement. Filling out the initial application is a crash course in many aspects of the NOP. Then maintaining those records over time can be a burdensome obligation as well. At first glance it’s easy to see how that might be a deterrent for some folks. Yet it’s the documentation that provides certified organic producers with the information they need to run more profitable businesses. Much as we hate to admit it, sometimes drudgery is worth the effort.

Some time ago I wrote that we’d decided to go through the organic certification process. The first task before me as part of that process, was to complete a variety of forms known as the New Application Packet. Those forms serve to describe our operation: how we manage different crops and livestock species, how we market our agricultural products, how the farm works day to day throughout the year, and how we protect the various natural resources on the farm. Those documents are the foundation upon which we demonstrate how our farm meets both the spirit and the letter of the organic program. So it’s a pretty big deal to complete the paperwork, and then maintain it over time. Those who have completed the organic certification process have said that the documentation portion was the single most difficult aspect of the initial application; get through that and the rest is relatively easy. Those same folks have something of an ongoing love/hate relationship with the documentation even after the initial application. The records are a pain to create and maintain, but they provide valuable information not only for certification renewal, but also for ongoing management of a profitable operation. Given all that, I wanted to give this documentation stuff as much attention as it needed; our certification would sink or swim on the basis of how well I completed those forms.

The biggest hurdle I faced was wrapping my brain around which forms were required. There are three producer-level categories of certification: Crops Production, Ruminants Production and Non-Ruminants Production. Crops Production could include anything from market veggies to fiber crops to grains to orchards and berries. It also includes hay and pasture. This becomes crucial for the second category of producers, namely Ruminants Production. One of the foundation principles for organic ruminant management is access to pasture - at least 120 days per year, and adequate roughage intake (ie, hay) during the rest of the year to enable normal rumen function. That hay and pasture must be certified organic. As a result, certified ruminant production typically goes hand in hand with certified hay production and/or pasture management. That relationship is so closely interwoven that a ruminant producer who wants to get certified, must also submit crops production paperwork to show how they manage their pastures. Even if they don’t normally consider themselves a crops producer. We knew we wanted to get our cows certified. That meant we’d already signed ourselves up for two of the three categories.

Yet we also wanted to certify our chickens, our hogs and our rabbits. All three of those species qualify as non-ruminants under the NOP, and would be managed according to slightly different NOP rules than the ruminants. So that required submitting paperwork for the last of the three categories - non-ruminant production. And that formed the bulk of our application packet - filling out details for all three aspects of our production. My first task, then, was to wade through and complete the documents required for each category. These documents would be our “photos” of how the farm worked, such that anyone would be able to look through them and get an idea of what we had, how we managed it from day to day, and how we anticipated, dealt with and/or avoided a wide range of issues that can and do occur during the year.

Each category featured one document, the Organic Plan, which served as the overall description of that category. For instance, our Crops Production Organic Plan included sections where we listed our yearly crops, described our rotation schedule, named our sources for seeds and transplants and cuttings, listed the pests and diseases we’ve dealt with in past years and how we’ve dealt with them, described our soil fertility programs, scheduled our estimated harvests, yields and income, and even called for maps showing the different fields and neighboring land usage. Similarly, the Ruminants Organic Plan provided places where we described our nutritional programs, our disease management methods, our housing methods, pasturing summary, animal production life cycles, etc. The Non-Ruminants Organic Plan asked similar questions but without the pasture element.

In addition to each category’s Organic Plan document, other documents within each category allowed us to provide much more detail than the summaries given in the Organic Plan. For instance, the Crop Producers Organic Plan asked for the companies who supply our seeds, but another form listed all the different varieties of seed used during any given year. The Ruminants and Non-Ruminants Organic Plans each asked for nutritional program summaries, preventative health care information and medical treatment practices, etc. Then associated documents allowed for more detailed information - a daily schedule record for pasture turnout, a medical treatment logbook, breeding and birth/hatch records, slaughter and/or sale records, etc. If I set up my record-keeping correctly, not only would these documents form an illustration of our operation, but they would also become a written history over time.

At first it was a challenge to figure out which documents applied to me, which didn’t, and which piece of information went where. At first the wide assortment of documents seemed overwhelming. But as I worked with all the documents, they became more familiar and easy to work with. At that point I simply had to fill out the relevant forms, set aside those forms which didn’t apply to me, and then double-check everything to ensure that I didn’t have any inconsistencies between forms. I also had to simply proof-read things to ensure that the different sets of information all matched up - this field’s map was matched to this field’s buffer information, etc. So for two months, during every late winter and early spring storm we had, I was at my desk, going over this-or-that document, figuring out how they all fit together to form a comprehensive picture of the farm, and finally filling each out in turn. Given that we were applying for certification in all three categories, the vast majority of documents applied to our farm in some way. It took a solid two months from my initial “let’s do this” to signing on the last dotted line, and mailing it off. There were 64 pages in the mailed packet.

Looking back on that exercise, I can see how some would be very irritated at the amount of work required. But frankly, I would have been disappointed had that process been any easier. Not to say I enjoy filling out paperwork. I certainly don’t. But if this organics program is supposedly the thorough, comprehensive, in-depth look at a farm’s operation, it’s going to take a certain amount of effort to capture and document that information. Had the paperwork been easier, or less detailed, it would have been easier to cheat, or fudge over details that didn’t really live up to the spirit or letter of the NOP. Furthermore, the value of on-going recordkeeping would have been drastically less, if the documents were only summaries instead of detailed inventories and itemizations. I found myself feeling rather satisfied that the documentation process really did lift up and look under every proverbial stone on the farm, to make sure our management met those high standards. If we’re really going for this “best of” certification, that examination needed to be demanding.

So now that the packet has been mailed off, the next step is to wait. Wait for the packet to be reviewed by a WSDA Organic Program staff member; that individual will become my main point of contact with the WSDA’s Organic Program. If the reviewer has any questions or concerns about our application, we'll need to work through those before we proceed. Once those questions have been answered and that review is completed, then we’ll schedule the inspection to verify that our documents match our actual operation. We hope to complete the documents review portion of things sometime in May, then have that inspection sometime in late June or early July. Fingers crossed…….

First Hog Butchering Session

April 15, 2012

Kelso's Meats, our local butcher shop. We contracted them to come do the butchering for our first batch of hogs. They did an outstanding job. We are very fortunate to have such a butcher's shop so close to us; many rural communities are not so fortunate. For those who have such local facilities, we encourage you to support those businesses if at all possible. Without such facilities, small scale agriculture is extremely limited in options for feeding the community.

Our first pig butchering session finally happened, and it went pretty darn well. Particularly when compared to our first scheduled attempt. On that particular day, the hogs wouldn’t come into the yard we needed them in, and a variety of other things happened that day to go down as one of the worst days ever here on the farm. Happily, things went smoothly this time around.

We had rescheduled the butchering session with the same local, family-owned butcher shop that we’d scheduled with the first time around. They had been very accommodating when we’d called them that first morning to say we had to reschedule. We’d also patronized their retail shop for years, and we were very pleased with everything we’d ever had from them. So we still had high hopes that they’d be able to turn our first litter of pigs into edible fare. Not to skip to the end of the story prematurely, they lived up to all those hopes, and more.

Butcher day dawned misty and chilly, but without hard rains. The hogs had finally moved into the yard adjacent to the driveway, two weeks prior, so they were well acquainted with that yard now. The only thing to be done at this point was to be home, direct the butchering crew to the yard, provide one last feeding to distract the pigs for the kill moment, and then stand back and let the crew work. And that’s pretty much what happened. Their fully-contained truck pulled in around 9am, positioned itself immediately adjacent to the holding yard, and the two butchering staff got all their tools ready in advance. I was ready with the morning feed, and the moment came. I wondered how I’d feel, after raising these animals for the last 7 months. I didn’t want to be nervous or squeamish. Immediately prior to the kill event, all was calm and I just wanted everything to go smoothly.

The pigs had their heads down and were chowing down on their breakfasts when the crew began to do the kills. One man had the rifle, and had the experience of putting down thousands of hogs, cows, and other livestock. I was very glad he was handling the task. And one by one, he would take aim, fire once, and one more hog would go down. It was actually very quiet, with the pigs not making any noise. I did suddenly remember that when pigs are shot in the head, they will go down like a sack of flour but flail around quite a bit. Ours certainly did. But at the moment the shot hit them, they were senseless from that point on. So each knock-down constituted a humane kill. That had been my main concern that morning.

Once the hogs had all been killed, the butchering began. And here again I was quite impressed with the experience and professionalism involved. The crew brought one pigs after another out of the yard, onto the driveway, and hung them up by their hocks, using a gambrel and cable running over a high swingarm to a powerful winch in the truck. Once hanging, the two men very quickly bled, gutted and halved the carcasses. The whole thing seemed to go very quickly, thanks again to the crew’s practice. In less than an hour, the crew of two men had killed and butchered our hogs, with everything going very smoothly. We couldn’t have been more pleased. By the time their truck pulled out later that morning, with our hog carcasses hanging in the back, we were very relieved that everything had gone so well.

But that was only the first half of the whole butchering process. Next, the butcher’s shop had to cut and wrap those portions of the carcass that didn’t need additional curing, and put those cuts into a brine that needed to be cured. This particular butcher wanted each buyer to call them with preferences for how each carcass would be partitioned into various types of cuts. Oddly, this is the point where my involvement with the process yielded to my husband’s culinary preferences. I just raise them; he turns the carcass into food. So he spoke with the butcher about how we wanted our half cut and wrapped. Approximately one week later, we got the call that our packages were ready. The moment of truth had arrived. Had I raised up good tasting pork?

I was delighted to eat the first of our packages, a package of pork chops cooked up on the BBQ on one of our first warm evenings. It’s an interesting thing, eating meat that we’ve raised ourselves. While I know some choose not to eat meat of any kind for a variety of philosophical reasons, I long ago decided that I was comfortable with the idea of eating meat I had raised myself. Yet this was the first time I’d eaten pork we’d raised ourselves. All the care and effort given to the sow’s maintenance, the fretting about building the first farrowing yard, tending the piglets as they grew, finally weaning them from their mom, and then finishing out their care as they grew so quickly. It had seemed a lot of work at the time, but finally here was the payback. Better yet, we started to get comments coming back to us from all the folks who purchased our hogs, after they too had started to eat the various meats. Every single one of them was thrilled with the meat, and they all asked me to please let them know as soon as we had another batch of piglets. That was even more gratifying than preparing our own meals. It’s one thing to provide our own food, and a wonderful thing indeed. But it’s a profound thing to raise food for others, and to hear from them that it was some of the best they’ve ever had. That’s what the last seven months have really been about.

As pleased as we are with this first batch of piglets, we have already determined some ways to improve on our practices. We plan to offer better protection during winter conditions, a concrete pad upon which the crew can do future butchering, and some slight changes to the feeding program so the piglets can grow faster. We are also looking forward to our next batch of piglets being managed under organic certification, which raises the bar a little more on their housing, their feeding, and their general care. One of the things I’ve always loved about farming is that no matter how well we do things, there is always room for improvement. And as pleased as we were with our first batch of piglets, we have many ways to improve. So that will be the focus for our future piglet batches. In the meantime, we’re sure going to enjoy this first batch of pork.

Feed Bill Challenge - Cost Effective Rations

April 7, 2012

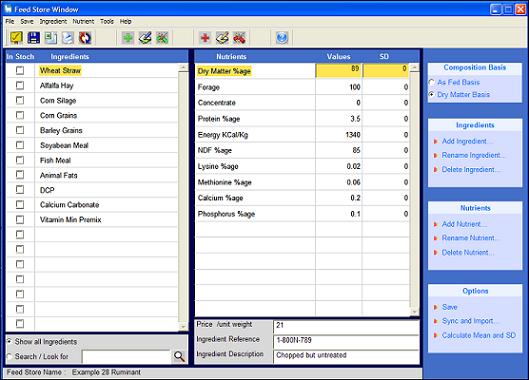

The above is a print-screen of a livestock ration software program called Winfeed. This program, and others like it, allow livestock owners to create, compare and evaluate different livestock rations, with different ingredients and different costs. That comparison allows each owner to develop a unique blend of rations for his/her own livestock. I'm evaluating several to determine which one works best for us.

My ongoing quest to cut the feed bill has looked for all sorts of ways to shave a few pennies, a few dimes, off the per pound cost of the various feeds we work with. Given that we go through thousands of pounds of feed per month, those pennies and dimes start to add up. So it’s definitely a worthwhile effort. In previous blog posts, we’ve already talked about some of the easier ways to do so - buying in bulk, buying direct from the grower, comparing different forms of the same ingredient, etc. Yet somewhere in the back of my mind I knew I’d come to this moment, when I needed to tackle a very big feed-related challenge. Namely, the challenge of formulating my own feed rations. And that moment has come.

Some folks would wonder why this is such a big deal. More than once, I’ve heard it said “just toss hay over the fence, give ‘em some grain and a mineral block, and it doesn’t need to be any more complicated than that.” For a lot of folks, that is absolutely true. A great many herds and flocks are maintained in very good condition, without a lot of complicated calculations required. But we’re setting a pretty high goal here - feeding the best possible ration, for the least possible money. The better the results we want, the more we’re going to have to tweak things. And it’s the tweaking that will either pay off handsomely in terms of cost effectiveness, or get us into trouble in terms of introducing nutritional deficiencies which end up costing us.

The first thing to know about formulating our own rations is that there are a lot of ways we can do it poorly. This is simply due to the fact that our livestock, generally speaking, can only eat what we give them. They can only build bone and muscle and hair and immune systems from the raw materials we give them. If the materials we give them are lacking in any way, or even if we give too much of something and too little of something else, they won’t be able to efficiently do the job we need them to do - provide the meat, the eggs, the milk, the fiber, and/or the work that we expect from them. That’s one end of the spectrum. The other end of the spectrum is that we do in fact give them everything they need, but it costs us so much in the process that we can’t make a living from our efforts. Our goal is to find that magical Goldilocks point, that “just right” point, where we are feeding just the right nutrients, in just the right combinations, in the most cost effective way, we can possibly find. And that takes some effort.

So, where do we begin? The first possible answer, and the one which many people choose, is to look through various well-regarded books for management of any given livestock species, and read up on that author’s recommendations. Some will only provide general information about the need for wholesome ingredients, providing enough protein, calories and minerals to provide for all the basic life stages. If a livestock owner has only one or two species, that study might actually be rather straightforward. Pigs, for instance, have very well documented dietary needs, and a number of books talk about how to meet those needs in a variety of ways. That would be the place to start. But that information is so general, it doesn’t give us optimized production, in the most cost-effective manner.

The next option would be to study more comprehensive livestock nutrition texts, such as the well-respected Morrison’s Feeds & Feeding. Various editions of this book have served as the basic college textbook on livestock nutrition since the early 1900’s. Each new edition included the latest research information on which feeds provided which nutrients, and how. Generations of livestock owners were trained with this book as their foundation, and it is still an excellent source of information today. I have two editions on my bookshelf- the 20th edition from shortly before WWII, and the 21st edition from shortly after WWII. I specifically chose those two editions because they provided a lot more information than previous editions, yet they were still focused on feed rations which would be either farm-raised or sourced locally. That philosophy of relying upon regionally available crops resulted in geographically-oriented tables and charts, showing which feeds were probably available in each particular region, and how best to combine those ingredients. Later editions began to include ingredients which were only available from distant locations, with the assumption that cheap transport options (which was true at the time), would make for the more cost-effective ration. That assumption is, in many locations, no longer valid. So once again, we are faced with trying to put together the best feed ration from the ingredients available locally or regionally.

While that textbook has served as the foundation for countless livestock owners, I found I couldn’t make use of that information as thoroughly as I had hoped to. I didn’t have the time it would take to read through, study, and really digest (no pun intended) all the different details for all the different species. If we had just one or two species to feed, that comprehensive study might have been possible amongst my other responsibilities. But with over a dozen different livestock species to manage here, there was just too much variability. I couldn’t justify the time required to read, understand and then make use of thousands of pages. Not if I was going to put together rations and get anything else done this year.

Fortunately, it turns out I didn’t have to. A third option is to use software programs to do all these calculations for me. At first, that might sound almost traitorous. Using software to calculate something this important? Turns out I certainly wouldn’t be the first one. I already know from conversations with others, that many (if not most) livestock nutritionists use one or more types of nutritional management software - from relatively simple Excel spreadsheets to full-blown multi-user software products with extensive databases. These software products store all the separate nutrient details for any given feed, such as the amino acid profile, the protein/energy/fat ratio, the types of carbohydrates, the types of fats and oils, the digestibility, the mineral content, etc. The software also contains all the general formulas, along with the more specialized information for which classes of livestock need which types of nutrients at different life stages. For instance, how dairy cows will need higher nutrient levels, particularly calories, protein, calcium and phosphorus during lactation than during pregnancy. How piglets need lysine to put on the most efficient growth after weaning. How rabbits will excrete excess calcium and sheep need much lower levels of copper than other classes of livestock. Various software products can combine and compare all that information, to help livestock owners develop just the right ration for each type of animal.

Furthermore, these software programs also allow us to track the cost of each ingredient. This way, we can compare different feed rations not only in terms of nutritional merit but also cost effectiveness. And best of all, these software programs range from simple do-it-yourself programs, where I download the template and put in my own data, to fully supported programs with staff to monitor and incorporate the latest and greatest research results. Of course the latter software is much more expensive than the former. I probably don’t need the bells and whistles they offer. Still, there are a variety of products for me to choose from, which will give me the data management I need, at a cost I can afford, at a complexity level I can deal with.

I am currently testing out a few different evaluation versions of such livestock nutrition management products. In a future blog entry I’ll write up which of them I ended up using, and why.

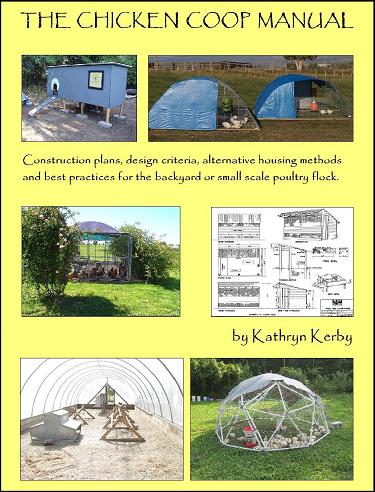

Our Successful Farming and Ranching Books

We released our very first self-published book. The Chicken Coop Manual in 2014. It is a full color guide to conventional and alternative poultry housing options, including 8 conventional stud construction plans, 12 alternative housing methods, and almost 20 different design features. This book is available on Amazon.com and as a PDF download. Please visit The Chicken Coop Manual page for more information.

Rabbit Colonies: Lessons Learned

We started with rabbits in 2002, and we've been experimenting with colony management ever since. Fast forward to 2017, when I decided to write another book, this time about colony management. The book is chock-full of practical information, and is available from both Amazon and as a PDF download. Please visit the Rabbit Colonies page for more information.

The Pastured Pig Handbook

We are currently working on our next self-published book: The Pastured Pig Handbook. This particular book addresses a profitable, popular and successful hog management approach which sadly is not yet well documented. Our handbook, will cover all the various issues involved with pastured hog management, including case studies of numerous current pastured pig operations. If you have any questions about this book, please Contact Us.