Going For Organic Certification

February 28, 2012

In a previous blog entry, I wrote about the different types of certification available to farms and ranches who aim to manage their land, their animals and their plantings in sustainable ways. I had frequently mulled some kind of certification over the years, and there are certainly a few to choose from. The idea of certification appealed to me, both for the recognition it would provide as well as for the standards we’d have to maintain to earn, then keep, that certification. Odd as it may sound, such rules and guidelines would sometimes be a comfort, or at least a reality check, as we try to juggle so many different projects and figure out how to keep the whole thing humming along in some coordinated way. But earning any sort of certification was always a lower priority at any given time than, say, getting a new hay shed put up, or getting the pigs bred, or getting the fence done, or any of the 1001 other tasks which pop up and demand attention at any given time. We weren’t in much of a hurry, we certainly had improvements we wanted to make first, and it didn’t seem to be hugely important to our overall operation.

That all changed with our recent pig sale.

As I wrote last week, we pre-sold our pigs through a distribution group organized by a friend of ours. During our conversations about the hogs, she asked if she could describe them as “organic hogs”. I told her that technically speaking, she couldn’t call them “organic” because we weren’t certified organic, even though we already met most if not all of the standards for certification. She then asked if she could describe them as “raised organically”, to reflect the fact that we weren’t certified yet held to those standards. I had to tell her no, because again that term is carefully regulated, and it implies not only meeting the standards, but that some third party has inspected and verified that we meet those standards. I could not in good conscience let her use any variation on that federally defined term, since we had never gone through that particular review of our operation. She was disappointed - many of the folks on her distribution list put value on the idea that they’re buying from farms and ranches that adhere to those higher standards. After our conversation, the question of how best to describe our practices stayed with me. As did the fact that of all the certifications available to us, the customers asked for and recognized the “certified organic” label above all others.

So then I started to ponder, what would it actually take for us to become certified organic? I had been dancing around the topic long enough that I knew most of the “biggies” - we needed to give our ruminants access to pasture for a good chunk of the year, we needed to maintain all our animals in species-appropriate housing, with free access to the outside, and feed them species-appropriate feeds which were also certified organic. We needed to use holistic methods for both prevention and treatment of any health issues. We needed to use either certified organic and/or natural products to fertilize our planting areas, and treat disease or pest problems with approved methods. We needed to manage our planting areas, and the farm as a whole, with an eye towards water quality, soil conservation, erosion control and fertility improvement. While that seems like quite a list, we were already meeting most of these criteria, and the rest were on our “to do” list anyway. The question of “could we become certified organic?” morphed into the question of “why haven’t we yet?”

I started to look at more of the nitty-gritty, and the reasons people have given for not going certified. Recordkeeping was a biggie, and for good reason. One of the ways that certifying agencies keep tabs on certified farms is via the records they keep - what materials and methods and management styles do the farms/ranches use? What sorts of results did they get when using those materials and methods and management styles? What were their production volumes, and were those production volumes reasonably possible given those methods? What problems did they have, and what solutions did they use to overcome them? In short, do the results reported agree with what the farm or ranch could reasonably produce using organic methods? Any sort of discrepancy would be cause for a closer examination. Merely compiling all that information would be tedious. Being told what to do, how to do it, how to report it and then weathering the inspections to prove it all - that would be a whole new quantum level of tedious. I could sure understand someone not wanting to mess with all that.

But the thought stayed with me that we’re already working at that level. Would the record-keeping really be that bad? My husband is a huge fan of records, and data crunching in general. He has often asked me detailed questions about this-or-that aspect of the farm, and I didn’t have the records to come up with a solid answer. I never liked that situation and neither did he - it’s hard to make good business decisions in a vacuum of information. So the notion of recordkeeping started to sound like a burden that would be in our best interests to bear.

The second major objection a lot of folks have is the limitation on what materials they can use to treat problems: pest and disease problems with crops, soil fertility problems, and health problems with livestock. Yet a review of our own practices and preferences over the years told me that we already “reached for” those solutions which we knew were acceptable under the National Organic Program rules. We used holistic methods almost exclusively with our livestock, we used natural fertility-builders for our soil, and we relied on soil fertility, mechanical traps, season extenders and certified organic substances to treat any sort of crop pest or disease. We could hardly claim to have record-breaking yields, but it was important to us that we weren’t solving a problem today by using a substance that we felt could create problems down the road. In short, we were already meeting the criteria that most folks find hardest to meet. Not because we had to for lack of other options, and not even because we had to for the sake of some certification. We met those criteria because we agreed with them, in letter and in spirit. So two of the biggest hurdles looked like they either wouldn’t be hurdles at all, or surmounting them would work in our interest anyway.

The last variable before deciding to apply, was the rental pasture. That is such an integral part of our operation that we couldn’t apply without including that parcel. Yet it’s not our parcel. We felt it was the right thing to do to get our landlord’s permission first. After all, we’d need his cooperation to get that parcel certified - he’d have to provide the affidavit that no prohibited materials had been applied to the land for the last three years, and that he’d agree to it being managed per the NOP rules in the future. So I called him one recent day and told him I wanted to come over “to discuss some tentative plans” I had for that parcel. He was intrigued to hear what I had in mind. I called on a Monday, and set our appointment for later that week. Those were the longest few intervening days I’ve experienced in a long time. Would he laugh at the idea? Would he be dead set against it? Had he applied something that I didn’t know about, which would sink the application? Would he be excited? Would he be irritated? Would it somehow violate our lease? I really didn’t know what to expect. I went over at the appointed time, and presented my proposal. To his credit, he was receptive and open-minded. He let me go through my whole plan without interruption, and he was silent for a moment afterwards, as if gathering his thoughts. “No matter what is response”, I remember thinking, “at least he heard me out.” And then the questions started. Careful, thoughtful, realistic questions. He was concerned the soil had some significant deficiencies; how did I plan to correct for those? Would the 14 acres provide enough hay and pasture to meet all my livestock’s forage needs for a whole year? That blackberry patch along the south fence line - how would I deal with that if I wasn’t allowed to use broadleaf weedkiller? Those questions, and working through my proposed answers, took up another whole hour. He then told me that he had occasionally thought of certifying his farm as organic, but the whole process had seemed too much, and he hadn’t been sure of how to solve those problems. He was far more than merely willing to allow me to proceed. Rather, he was very supportive and encouraging; I had his full blessings to proceed.

Armed with that last requisite piece, I knew the time had come. I drove home, fired up the computer, called up the state’s organic program website, and started downloading all the application materials. We were going to go for it.

In future blog entries, I’ll write up more detail about the process of applying for organic certification: any frustrations we may have, obstacles we may discover, and the experiences we gather along the way. Whatever comes of this application, just going through the process will be quite a thorough review of our operation. I expect it’ll be quite a ride.

The Value of Pre-Selling to the "Right" Market

February 22, 2012

They say that growing the crops and raising the animals is the easy part of farming. The hard part comes when you try to sell those products you’ve worked so hard to create. And to sell them at a price that accomplishes the impossible: high enough to not only cover costs but also reap at least a little profit, low enough to keep the customers happy, even enough to be on par with what your other regional producers are charging, and flexible enough that if some piece of this puzzle changes, you can change too.

That’s a tall order. Yet that was the order of the day when the time came to set the purchase price and start selling our near-ready market hogs.

My first move was to figure out how much we’d spent on them so far, and how much more between now and slaughter. Our sales price had to cover that cost, at a minimum. Thanks to the work I’ve been doing studying our feed costs and patterns, I was able to put together a fairly accurate estimate for how much they have cost from birth to market date. It matched up fairly well with published figures that I was able to find online for the amount of feed required to bring market hogs to market weight. OK, Step 1 was done.

Step 2 was figuring out what the going market rate was for market hogs, and how they were sold. I had seen flyers posted around town at places like the feed store, the butcher’s shop, and in various neighborhood classifieds such as Little Nickle and craigslist. Prices varied, depending on the age and size of the hog, and how it was being sold. WA state law allows hog producers to sell by the whole or the half, and that’s how the vast majority of others marketed their hogs. I found enough ads during my search that I was able to set up a pricing structure that would cover our costs, make us a bit of profit, and still be about par with other sellers.

Just as a reality check, I submitted my marketing ideas to a small scale hog producers list that I’m on, and asked for feedback. Several folks responded, including two producers near me, one of which was in the same county. They all shared the opinion hat my prices were too low, and that I should raise them just a bit. Not only would that provide a better return on my investment, but they also pointed out that low-balling the market was not the way to build a reputation for quality. Furthermore, they reminded me that the customers I make now are hopefully going to become repeat customers. It would not reflect well on us if we had a low price this time around, only to raise prices later. Set those prices where they need to be the first time out of the gate, and then ongoing customers wouldn’t be surprised. So, I took all that advice, wrote up a nice sales blurb, and posted my ad in the regional craigslist. And waited.

I started to get calls about a day later. The calls were all about the same - they’d seen the ad, they were interested in buying, but they had never done this before and they had questions. One of my hog list members had warned me that first-time buyers often required a great deal of hand-holding. So I was expecting this to a certain extent. I called them all back, walked through the purchase options, answered their questions, and got the same uniform answer from all of them - “we’ll think about it and let you know.” And that was the last time I’d hear from them. I started to get nervous.

After almost a week of this, I started to think that I needed to reconsider my strategy. I was reaching a wide variety of possible buyers, but I clearly was not reaching the right clientele: folks that were already comfortable with the idea, knew what they wanted, knew the price was good, and were ready to buy. But where to find them?

Almost as an afterthought, I contacted a friend of ours who runs a bulk foods buying group for a church congregation about an hour south of us. We had been receiving her newsletter for years, and we had participated in a variety of bulk buys from her in the past - dry goods like grains and beans, fruits, canned and dehydrated goods, etc. We knew that she hooked up buyers and sellers for meats too. That was exactly what we wanted, and I was embarrassed that I hadn’t thought of contacting her earlier. I sent her a short email about what we had and when it would be ready, and kept my fingers crossed.

She emailed me back within a day or so, and said yes she could certainly put out the word for us that we had market hogs for sale, but our pricing structure was a little different than her group was accustomed to. She described their pricing structure and asked if that alternate arrangement would be satisfactory. At first, I resisted the idea. I had worked through my numbers pretty carefully - why should I accept something else? But then I took the time to work through her pricing structure, and I’m glad I did. Under her pricing system, we’d get more from our sales than we would have through our craigslist ad. I emailed her back and said yes, that pricing would be fine. And then the amazing happened. Less than 24 hours later, she emailed me back and said she’d sold our hogs. It was that easy.

And herein lay the lesson. When we were reaching out to the wrong crowd, we received nothing but questions, and even after answering the questions no one was ready to commit. When we found the right crowd, not only did they already know how the process worked, they were ready, willing and able to write the check. I had my deposit checks within 4 days of our friend putting out the word to her distribution list. So it’s not just a matter of going through the motions and checking the numbers to make sure everything adds up. It’s not even a matter of reaching “enough” people. It’s a matter of reaching “the right people”, in terms of customers who already know what they want.

So we head into our last few weeks with this first batch of market hogs, enjoying the comfort that only comes from knowing they are already sold. I can’t describe how fantastic that feels. I can say that if we hadn’t gotten them sold, I would have gotten increasingly nervous as their butcher date approached, because we would be on the hook for selling all that meat, and running out of time to do so. Happily, we make the connections we needed to make. Better yet, that same connection is also interested in whatever else we have for sale in the coming months. That right there is worth gold - having a market ready, willing and able to buy whatever we produce, at going rates that cover our costs and guarantee a bit of profit.

So, Dear Reader, if you are wrestling with how best to either buy, or sell, a variety of farm products, we now can wholeheartedly recommend at least exploring any bulk buying clubs you may have in your area. Churches, office buildings, social clubs, even Yahoo groups are forming all over the country to connect buyer with seller in ways like I’ve described above. It may not work for everyone, every time. But it worked extremely well for us this time, and we look forward to working with our particular buying club in the future.

Workshops, Meetings and Other Distractions

February 15, 2012

The above is one of my favorite paintings from one of my favorite artists, Norman Rockwell. He had a talent for capturing potent human emotions, behaviors and activities, in ways that people can instantly identify with. The above painting is entitled “Freedom Of Speech”, painted in 1943, as part of his “Four Freedoms” series. It celebrates the right, and responsibility, of people from all walks of life to participate in community policy building. It is an image that I have held close to my heart for a long time. Even as I take a break from such participation, I look forward to being able to resume my rights, and responsibilities, in this topic. To read more about this image and Norman Rockwell in general, please visit The Norman Rockwell Museum.

There is a lot to be said for learning at the feet of the master. When we absorb lessons learned the hard way by others, we can avoid “reinventing the wheel”, and we can make more rapid progress forward on this great learning curve called farming. The dissemination of information has never been easier than it is now, and books, downloads and video streaming certainly has a role in training the next generation of farmers. That being said, there’s still nothing quite like going to a workshop, being surrounded by folks who have been where you want to go, and/or folks who are trying to learn the same things you’re struggling with. The camaraderie that forms within such groups can be a powerful motivator. And the information shared can be astounding.

Similarly, there’s a lot to be said for getting involved with local, regional, state or even national groups who are working in some way to protect or advance sustainable farming efforts. Farming has never been easy, granted. But we face unique pressures now that our predecessors never experienced. Those pressures can drive policies, laws and regulations which either make our work harder, less profitable, and/or outright forbidden. Our nation was founded on the notion of public involvement at every level of government, and that is still true today. I have long advocated, here and elsewhere, that people need to get involved in the policies that affect their lives. It’s a lot of work, but it is our first best solution for ensuring that government policy works for us, or at least with us.

Having said all that, however, there is a point at which we have to stay “Enough”. I reached that point this year.

We definitely fall into the category of “beginner farmers”. I’ve written in a recent blog that I’m not even sure I’ve earned the title “farmer” yet. So when these workshops have come around, through either our state’s land grant university, our county extension office, or other regional agencies and entities, we’ve usually attended. Whether it was pasture management, cover crops, small grains, poultry processing or market veggies production, we figured we had something to learn. And we learned a tremendous amount each time. So when this year’s workshop schedules were released, my first inclination was to attend as often as possible. But then I started to really consider - at what cost? Many of these were workshops similar to those I had already attended. It would have been wonderful to visit with the folks I’ve met over the years, learn the latest and greatest in various topics, get the scoop on new policies or regulations in the pipeline, and otherwise enjoy the time spent “talking shop”. But I could also spend that time actually getting stuff done around here. Whether it was building fence, repairing existing buildings, building new shelters, or trimming hooves, there was definitely work to be done that wouldn’t get done if I was off-farm. A review of the to-do list, versus what I’d likely gain by attending the workshop, almost invariably came back in favor of staying here and getting things done.

I had the same experience when encouraged to attend various meetings. I’ve written in the past about how attendance and participation in these meetings is, I believe, a responsibility for us all. I’ve logged a lot of hours with such groups, working to build new ag processing facilities, changing county or state policy, giving informed comment to government officials as they deliberate laws and regulations, and compiling information and documentation as evidence to support advocated changes. I don’t regret any of that effort. Yet when I looked at the issues before us at the moment, the people already involved in making changes, and the agendas for the various groups, I realized that my participation there would be minor. My participation here would be crucial. The logical choice, at least over the short term, was to focus my attention here.

It’s a hard call, deciding where to invest the limited time and energy we have at any given point. I definitely felt the pull to participate in all these activities, and I never doubted the value of doing so. But perhaps one of the most crucial lessons I’ve learned so far, is that we can’t do it all. No one individual can be everywhere they’re needed, attend to every issue of interest, and make the most of every new opportunity that trots down the road towards us. We can only do so much, and learning our boundaries is as crucial a lesson as any of the rest of it. Right now, the farm needs my attention if it is to thrive. That’s a hard reality. If I put things on hold in favor of learning some new thing, I won’t be able to put that new thing into place if the farm isn’t up and running to take advantage of it. It becomes a catch-22. All these fine lessons learned about how to run a farm better, requires an up-and-running farm to begin with. So this year at least, I’m going to focus on putting all my existing knowledge and lessons and how-to wisdom to work. I have no illusions that we’ll get it right the first time. We won’t. But we’ll get it up and running. Once we reach that point, THEN I’ll feel better about taking some time to go learn how to do it even better, or go advocate for policies which protect and encourage this sustainable farming way of life. But until then, my time and my energy belong here.

2012 Feed Bill Challenge - the January Report

February 7, 2012

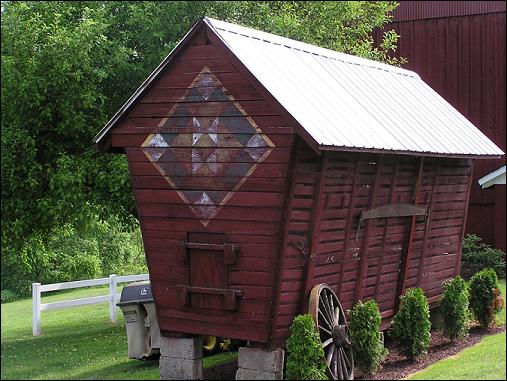

An absolutely gorgeous old corn crib, well tended and painted in 2011 with a quilt design by barn artist Scott Hagan of Ohio. Corn cribs were traditionally used to store corn between harvest and feed-out. They had to provide rugged protection against wind, rain, snow, sunlight and rodents. While entirely utilitarian, they could also be quite beautiful as Scott’s work can attest. Note the slope of the walls which ensured the contents would stay dry even during driving rain, and also note the small door in the front wall, through which the contents could be removed a little at a time. For more information on Scott’s wonderful work, please visit his website at barnartist.com. Plans for small-scale corn cribs and other grain storage bins can be found online by Googling “corn crib”, “grain storage” and similar terms.

Our first month’s close-up look at the feed bills yielded some surprising results, and opportunities.

First of all, it turns out that tracking our feed bill has been difficult, in part because of how I have built our feeding program. I tracked exactly how much we spent on feed in January; that part was easy. But how was that feed used amongst the various animal populations? I decided a long time ago that I wanted to build our feeding program on items that we could either purchase, or grow ourselves. So I purchase bagged whole feeds, such as scratch grains (wheat, corn, oats, barley), COB (corn, oats and barley), alfalfa pellets, cubes or bales, sugar beets, sunflower seeds, split peas. That part has worked out well, because we have definitively concluded that we can maintain our animals on feeds we can grow ourselves if we choose to do so. However, I mix-and-match those ingredients in custom blends for each category of livestock, and that blend varies over time. For instance, we feed more alfalfa and sunflower seeds during the cold months. We also feed any given blend in varying amounts depending on the weather, the age/growth stage of the animal, the physiological state (dry, pregnant, lactating, growing), and even the marketing stage (putting on weight, trimming down weight, adding a “bloom” prior to sale). Given all that variation, we can’t simply look at our feed receipts and tell how much a particular animal used a particular feed. If we’re serious about tracking these costs, we have to either stabilize the recipes, or measure and document every last ounce of feed we use, and who we feed it to.

A second surprise was the variation in cost amongst feed ingredients. I could easily understand that higher quality feeds, ie those which had higher levels of protein, would cost more than coarser feeds. What surprised me ws that so-called complete pelleted feeds were cheaper than whole feeds of roughly equal nutritional value. Perhaps that part should not have surprised me. I suspect that complete pelleted feeds are sold in much greater volumes, which thus would help keep the cost lower simply by working with greater efficiency of volume. For instance, we switched from a complete hog feed to a home blend years ago, because we wanted to make sure we could maintain our hogs on homegrown feed. But that complete hog feed is cheaper by almost 30% when compared to the mix we’re currently using. Wow! Given that we’re growing out our first batch of market hogs, which means putting roughly 4lbs of feed into every new pound of hog flesh, that single price difference makes a huge change in the weekly cost.

Yet that rule had a few exceptions. We feed a lot of alfalfa in various forms: bales, straight pellets, cubes, and an complete feed, alfalfa-based pellet with balanced C:P ratios. Not surprisingly, the straight bales were the cheapest; in our area they priced out at $0.21/lb. The second-least expensive was the straight alfalfa pellets, at $0.30.lb. The next most expensive was the complete feed alfalfa pellets, with the correct C:P ratio, at $0.33/lb. The most expensive was the alfalfa cubes at $0.34/lb. I had been feeding that a lot because I figured it would be less expensive since it was less “altered” from the original form. Also, it was marketed in a 40lb bag rather than a 50lb bag, so it was slightly cheaper PER BAG than the other forms of alfalfa. But on a per-pound basis, it was the most expensive option.

Finally, I confirmed something I have suspected for a long time, namely, that buying feed by the bag is the single most expensive way to do things ever invented. Purchasing feed by the bag is many, many steps removed from buying it direct, and every step adds something to the cost. Conversely, every step we can peel away from the core cost, the more we can save ourselves. For instance, I buy X number of bags of feed from the feedstore at a certain standard retail price. If I merely buy that same feed, from that same retailer, in the same bags, but still loaded on the pallet, I get a 10% discount from that particular retailer. If I buy from the mill, rather than the feed store, I can knock off another 10-20%. If I get those same grains from that same mill in bulk form, rather than in bag form, I get yet a better discount. And if I buy straight from the farmer that grew them, that’s the cheapest of all, even if it’s the same grain sold to the mill.

However, there’s a fairly significant second issue involved: convenience. And this comes in many forms. If I buy feed bags on the pallet, I have to have a way to lift, move and stack pallets weighing up to a ton. That generally means two things - a forklift, and a heavy flatbed truck which can handle the weight. We have neither at the moment, although our tractor could be mounted with a three-point-hitch forklift. The flatbed is another story. We’re already investigating that possibility for a variety of reasons, but it’s not something that is going to happen overnight. So that right there limits our options. However, one of our regional certified organic feed mills also offers a delivery service, at prices which are competitive with even the local conventional feed prices. That option is quite attractive; we’ve used their service before. We eventually switched to bagged feeds from the local feed store only because we drove past them on the way to/from work every day. Now that my work is here, I have to re-examine that logic and that pricing.

The other issue with buying bulk is - where to store it all? During February, we used five different types of bagged feed, dozens of bags of each. We have a row of 10 metal trash cans in which to store the feed to protect it from wind, rain and most importantly - rodents. That system has worked fairly well for us until now. But as we get bigger, and particularly after we start growing our own feed, that storage will be woefully inadequate. We’ll need both a root cellar in which to provide either cold-and-dry or cold-and-moist storage for a variety of crops, as well as much larger bins in which to store dry grains. A corn crib is a traditional, yet practical, way to safely store corn in the ear until it is needed. Well designed cribs are easy to load, easy to unload, and provide good ventilation yet protect the crop from weather, heat and rodent damage. All these storage facilities must be in place before we switch over to bulk purchases in any form.

So after our first month of carefully monitoring our feed, and looking at what that feed costs and how to cut costs, we clearly have our work cut out for us. Happily, that effort will yield considerable savings. It’s one thing to see a lot of work ahead; it’s another to see the savings such work will provide in the long run. We don’t need much more motivation than that to get these projects underway.

Our Successful Farming and Ranching Books

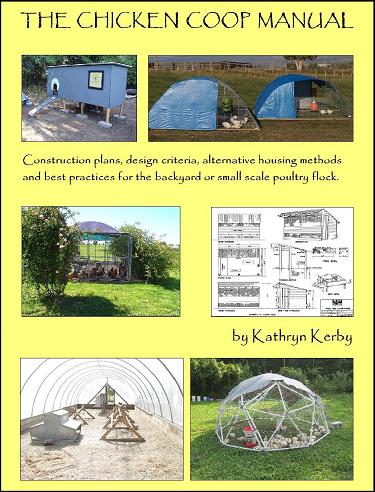

We released our very first self-published book. The Chicken Coop Manual in 2014. It is a full color guide to conventional and alternative poultry housing options, including 8 conventional stud construction plans, 12 alternative housing methods, and almost 20 different design features. This book is available on Amazon.com and as a PDF download. Please visit The Chicken Coop Manual page for more information.

Rabbit Colonies: Lessons Learned

We started with rabbits in 2002, and we've been experimenting with colony management ever since. Fast forward to 2017, when I decided to write another book, this time about colony management. The book is chock-full of practical information, and is available from both Amazon and as a PDF download. Please visit the Rabbit Colonies page for more information.

The Pastured Pig Handbook

We are currently working on our next self-published book: The Pastured Pig Handbook. This particular book addresses a profitable, popular and successful hog management approach which sadly is not yet well documented. Our handbook, will cover all the various issues involved with pastured hog management, including case studies of numerous current pastured pig operations. If you have any questions about this book, please Contact Us.

Weblog Archives

We published a farm blog between January 2011 and April 2012. We reluctantly ceased writing them due to time constraints, and we hope to begin writing them again someday. In the meantime, we offer a Weblog Archive so that readers can access past blog articles at any time.

If and when we return to writing blogs, we'll post that news here. Until then, happy reading!