Farm Insurance

March 31, 2011

I have written in numerous past blogs that farming can simultaneously be a career, a lifestyle and a business. Particularly with the business aspect of things, occasionally we need to step outside of what’s average or normal or familiar, and deliberately seek out new ways of doing things or organizing things. This attempt to “push the envelope” of the familiar is ultimately justified when we subsequently function more efficiently as a business. It was with that goal in mind, that we started to look into switching from homeowner’s insurance to farm business insurance about a year ago. It’s been an interesting ride since then.

This all started in a class I took last year called Cultivating Success. That class, offered through my county Extension office, assumed students were already competent in various animal and/or horticultural operations, methods, and/or products. The point of the class was to expose us to the business aspect of our various farming/ranching operations - the legal, marketing, liability, regulatory and financial details we needed to run a profitable operation. The class was quite rigorous and we learned a lot. One of the presentations was from a farm insurance agent who talked about the various types of property and auto insurance, and why we should consider switching from a standard residential policy to commercial and/or farm policies. The reasons were compelling - better coverage for buildings, equipment and infrastructure other than our main residence, coverage for the main residence which often also doubles as a place of business, coverage for weather damage, liability/loss coverage in case of visitor injury, livestock escape or vandalism, and perhaps most important of all, coverage in case one of our products resulted in injury or illness for a customer. Similarly, switching private vehicle insurance over to business vehicle insurance would cover not only our vehicles but also whatever we happened to be carrying at the time - livestock, feed, product, etc. Best of all, those policies are often slightly less expensive than the standard policies we’d been carrying. What’s not to like?

As with many things in life, our best intentions got sidetracked. That spring, like every spring, was chock full of gotta-do’s. Anything not on the gotta-do list was eventually put on a back burner. Our plans to research and switch policies languished on the proverbial “I’ll get to it someday” shelf. That all changed on May 4th, 2010, when a rare late spring windstorm, blowing out of the northwest, took out a huge old cottonwood on our property. That cottonwood fell on the house. I’ll write up that experience in a separate blog entry. But in this context suddenly our insurance coverage took on a whole new meaning. The damage to the house was extensive. Multiple branches pierced the roof. Other branches crushed the corner of the house (my office), destroying the siding along two sides. The pressure changes as that huge canopy came down blew out windows. And worst of all, a variety of small but valuable farming equipment was crushed and buried under tons of secondary branches. Our insurance policy was about to be thoroughly tested.

To make a very turbulent long story short, all the repairs to the house were done promptly and without question. The real issues came up later. The first issue arose about coverage for that equipment. I was able to convince the adjustor that the equipment was for gardening, which any homeowner could reasonably have alongside the house or in adjacent yards. That was settled separately from the house repairs and I have no complaints. But when we started to review the “could-have-been’s”, things got more serious. The tree had missed one of our primary growing areas by mere feet. Had the wind direction been just a little different, I would have lost my entire market garden area and possibly our honeybee hives, mere days before our markets opened for the year. That lost product, growing area, equipment and income would not have been covered because it would have been a business-related loss, not a residential loss. Secondly, the wind direction also spared one of our main barns, which had already previously been hit by branches from a different tree. That first hit killed one of our sheep, and it had been a relatively small branch. If this huge old tree had hit the barn, we could have lost both the goat and sheep flocks, with no coverage from the insurance. Clearly, it was time to take another look at switching policies.

We still had one holdout consideration - the residential insurance coverage company we had at the time had been wonderful to work with during the claim. They didn’t offer farm policy insurance. Did we really want to jump ship after they had just delivered so well? Oddly enough, they answered the question for us, by canceling our coverage a short time later. Supposedly, an adjustor had driven by the house sometime during the repairs, and pronounced that certain things had not yet been completed to the company’s satisfaction - the roof was covered with moss, the front yard hadn’t been mowed, and debris in the side yard hadn’t been cleared away. I called my agent and questioned that report since the roof was brand new (hence, no moss) the front yard was a garden (hence, no lawn to be mowed) and the “debris” in the side yard was possibly the equipment that had been smashed into the ground by the falling tree. He said the adjustor may have simply reported on the wrong house, and he could certainly contest the findings. But then he asked the question that signaled the beginning of the end of our policy - “your voicemail said something about ‘thanks for calling the farm?’ We don’t cover farms.” My agent and I decided at that time that we were well on our way to being a farm, and as such we really needed a farm policy. So with mixed feelings about the whole thing, I agreed to forego his challenge of the policy cancellation, and simply replace our residential policy with a farm policy instead. Easier said than done.

My search for a farm policy seemed simple enough, but that was not the case. My first call was to a company affiliated with our state Farm Bureau, which seemed a logical place to start. That agent came out to the farm, dressed in nice suit and nice shoes, and proceeded to stand in the driveway trying not to step in mud. Which, given our driveway and given that it was February, meant he didn’t move very far. I spent an hour with him going over all the outbuildings, equipment, livestock, growing areas and earnings for our place. He took down all the information to generate the policy quote, and drove away in his nice little car. And I never heard from him again. Hmmm. Called another agency which supposedly specialized in farming operations. Most of their offices were devoted to residential and non-farming-business insurance, but yes they did have a farm specialist, in a town about three hours away. Yikes. So I called them and burned up a lot of telephone minutes going over the same list. They called back three days later to ask if I would be willing to drop my egg and meat sales. Excuse me? Apparently, egg and meat sales are “high risk” so they were having trouble finding an insurance carrier for those. “Uh, my egg sales generate a lot of my income during the off months, and I’m licensed as an egg handler by the state. So the risk should be a lot less than some Joe Shmoe selling them at a farmstand. And our meat sales are to a regional zoo, not for human consumption. So how is that a risk for human illness?” Those questions seemed very logical to me but apparently logic has little to do with insurance adjustors. They never were able to find a policy for me that would cover those income streams.

Finally in desperation, I emailed one of my national farming email lists, asking other growers what insurance companies they used for their businesses. Amongst the replies I got referrals to two companies which had apparently worked out well for the farmers using them. One of those companies did not do business in our state. The other was one of the larger companies, and their website looked very much aligned with commodity farming and large commercial operations. I wasn’t sure they’d work out either. But they had an office only 20 minutes away, and my initial phone calls went quite well. Perhaps I had finally found my new insurance company. Meanwhile, back at the homestead, our residential policy did in fact expire while I was hunting down these other possibilities. When the first two companies couldn’t provide farm coverage, I called my residential company back and asked if there was some kind of extension available. “Oh, no, once a home policy is cancelled, we can’t create a new one for you. Nor will any other residential policy company. Sorry.” Well, that sealed it. We were either going to have a farm policy or, apparently, none at all.

Thankfully, that third company came through for us. They were able to provide coverage for all our existing operations, plus dairy and meat sales to the public which are both in our future plans. They also provide coverage for farm vehicles which we’re still lining up. Our coverage for both will be slightly cheaper than the residential/private policies we had previously. And best of all, we’ll have coverage for all aspects of our operation, not merely the house. That new policy did come with a long list of activities and income streams which are prohibited. Fortunately, none of those activities are on our list of current or planned income streams. But I found it interesting that many of the income-stream alternatives being given to young/new farmers and ranchers, are also categorically denied by the same insurance industry that we’re encouraged and sometimes required to use. Activities like agri-tourism, on-farm hunting, boarding stables, etc, are all prohibited by the policy I was finally able to line up. I guess the moral of the story is that yes, farm policy insurance is an important piece of the farm business puzzle. But look well at your business, and your insurance options, before sinking a tremendous amount of money in activities that will leave you exposed to uninsured risk. Buyer beware.

Babysitting the Farm

March 28, 2011

“Life is what happens while you’re making other plans.” - John Lennon

My farming partner and I have been working well together so far. I’ll go down to her farm several times a week (more frequently now as the season is getting underway) and we’ll work together to launch this year’s crops in both the greenhouse and out in the planting beds. Then I’ll return home and tend the farm here, sometimes working fairly late to get everything done. If we had no outside interruptions, we would be well along in our plans for the year. But as it turns out, no one is quite so lucky.

She got a call about a week ago that her family needed her presence, as her father faced some new and serious health issues. So the decision was hastily made to leave mid-week and head for home, roughly 400 miles away. I would babysit her farm in her absence, ensuring that all the plants were tended, continue our planting work and generally keep an eye on things. She was gone for five days, during which time I got several cool-season crops planted, some additional bedding plants prepped, some things transplanted, and kept everyone watered. It was an interesting week during her absence, where I had to make a variety of small decisions about how to manage this or that on her farm, without her there to verify the decision. We talked during the day by phone and at night via email, but still her absence was noticeable. Upon her return, all was well and she commented that yes, this, that and those other things had been done well. A few things had not quite been handled the way she would have handled them but they were OK, and one or two items had gone completely unnoticed by me but would have been taken in stride had she been home. It’s never quite a perfect report card, when someone babysits for another’s farm. We all have our particular ways of doing things. But I for one was glad that she was home, and even more glad that she was generally pleased with the condition of the farm upon her return.

We have not traveled in almost 3 years. Our last trip was, ironically, much like my farm partners - an emergency trip home during a family health crisis. At that time we had been using a farm sitter who had done a really nice job for us, but she was unavailable during that emergency trip. My best friend’s daughter had expressed some interest in the farm and farm-sitting for us, so she got a crash course in how to take care of everything. My husband stayed home so he was there to provide for the house animals and to help her out for the rest. Still, it was a stressful trip for everyone because we had not prepped very well for my absence.

The topic of farm-sitting is something of a sore spot for us, and for many farmers, livestock owners and growers of any scale. We form such individual bonds with these living things we care for, and such closely tailored methods for providing their care. It’s hard to step away from that even under duress, let alone simply for the sake of recreational travel. My farm mentor had long wanted to travel to Africa simply to see the wildlife and the cultures there. It was a lifelong dream for her. Despite her close connections with her local 4H group and countless young farming enthusiasts, it took her years to establish the correct team of people to care for her farm when she finally decided to take that trip. She and her husband were gone for three weeks, and had a great time. When she returned, the farm was generally in good shape but one of their cats had run away (miraculously to be found months later) and she spent a fair amount of time putting things back the way she wanted them. It’s always a mixed bag of “thanks for watching things, but darnit I wish you’d done things the way I wanted them done.”

We wrestle with how best to set up our own operation, so that we can travel again. We don’t really care to travel for sight-seeing, per se. However we do want to visit distant family and friends whom we have not seen in years. The first task is to set up our operation so that the feeding schedule, the animal yards, the garden and the house are all set up efficiently and simply enough that anyone can easily come through and complete the tasks at hand, without remembering a whole litany of exceptions and special instructions and alternative rules. That effort also pays off in faster chores for me anyway, but it’s easier said that done. Buildings, fences, feeding programs and crop rotations are all impacted by the desire to streamline the daily chores. Yet even after that make-over is completed, we still need to find someone to actually be here in our absence. And therein lay the bigger problem. Most folks who advertise as farm-sitters are willing to watch a few horses, or a backyard of goats, or a small flock of hens. Rarely are people willing, let alone able, to walk onto a farm and know what they need to know to take over for a few days. Not unless they already work there or work at a very similar operation. At that point they are no longer called farm sitters. They’re called employees, and need to be paid (and in many states, insured) the same as employees. The quest for a long weekend turns into a long lesson in employee training and paperwork. Even if we got that part of things figured out, then there’s the issue of cost. We need to pay the employees who watch the farm. We need to forego the lost sales and marketing contacts which would be made if we were home and open for business. And sometimes we need to pay for the additional supplies, feed and other what-not that we’d get, use and replace during that time interval. Which in sum is why we haven’t left in three years. At some point, it’s just easier to stay home.

Nevertheless, there are family members to be visited, emergencies do come up, and darnit there are conferences and workshops and regular pretty places that I’d like to attend some day. So the quest continues to redesign the farm, train the farm babysitters, and sequester the money and materials required to some day step away for awhile. If and when that day arrives, I’ll need a vacation simply to make up for all the work I did preparing for the vacation. Here’s hoping I get all that done before Life happens to toss another emergency our way.

Foraging For Fun, Food and Profit

March 24, 2011

I had always been interested in wild foods. The notion is both ancient and cutting edge - gathering nutritious, tasty food from the landscape as a regular contribution to our daily nutrition. Now that I’m raising food as my income, that practice took on new meaning. In addition to our regular planted crops, it made sense to at least look into what might be growing already, and whether it could be marketed. Turns out, we had a lot of edible plants growing wild on the farm. But what could we do with it?

Last year I asked my market manager if I could bring some wild greens to market each week. In addition to being a farmers’ market manager, she’s also a regional authority on native cultures including the foods they foraged. I gave her my list of proposed greens - nipplewort, narrow leaf plantain, chickweed, dandelion, and dead nettle. All of them were nutritious, none of them were toxic, and each of them contributed a different shape, texture and taste to any particular blend. We also had plenty of each. She agreed, and I bagged up a few salad mix bags’ worth to take to market. I wasn’t sure what to expect, but I sold out that first time. Wow! So that next week I bagged up a little more, knowing full well that the previous week’s sales could have been nothing other than the novelty of it all. But again, I sold out. I brought those wild greens to market for the rest of our season, and each week they sold out, both to repeat customers and to new customers. I couldn’t believe it. Here had been plants I’d been weeding and discarding all this time, and they were selling at a higher price than the plants I’d seeded, weeded, tended and irrigated so carefully. Additionally, I had people tell me that they loved the taste, they loved the way the greens made them feel better, and they even sometimes asked for two or three bags for a party they were hosting. By the end of the season, I had become known at market as “the one with the wild foods” and I was getting requests for wild items which I did not have - fern fiddleheads, moss for terrariums, foraged mushrooms and rosehips to name a few. I came away from that season with a much healthier respect for wild greens, and the role they can play not only in food sustainability, but farmers market profits.

There is a very small list of cautions which I nevertheless should share. First of all, I had to harvest those greens from areas of the farm where we didn’t have any possibility of animal contamination. That cut out a lot of potential harvest area. This year we actually transplanted some of the nipplewort rosettes into the garden so that we’d have plentiful supply of them in a safe-from-animals crop production area. Second, we had to be absolutely positively sure on our wild plant identification. Some plants like narrow leaf plantain and chickweed are extremely common and easy to learn. Nipplewort has a very distinctive leaf and while relatively unknown, is also common and easy to identify. Wild mushrooms, however, will not ever be on our farmers’ market table because many very poisonous varieties grow here, and look very similar to culinary varieties. I won’t take that risk. And some, like the fern fiddleheads, are only available during a very short period of time. We may or may not offer those this year, depending on whether I have the time to harvest them when they’re ready, and if we have demand for them when they’re available.

If you are interested in wild and foraged foods, either in general or in your particular area, there are a variety of books now available to help you with your search:

Nature's Garden: A Guide to Identifying, Harvesting, and Preparing Edible Wild Plants

Nature’s Garden is written by one of the foraging community’s best respected authors, Samuel Thayer. His first foraging book, Nature’s Harvest, was hailed as the best of it’s kind, and used as the first best source of authoritative information on foraging for edible plants. That book came out in 2006. This latest book, released in early 2010, built on that previous success but added to it, and is now widely regarded as the best of its kind and far ahead of the rest of the pack.

Edible Wild Plants: Wild Foods From Dirt To Plate (The Wild Food Adventure Series, Book 1)

Edible Wild Plants is another well regarded and strongly recommended book on the topic. Excellent photos to help illustrate various forage plants goes along with humorous writing and tasty recipes. Perhaps not as scholarly a work as Nature’s Garden, but definitely also worthy of a forager’s attention.

The Essential Wild Food Survival Guide

This book by Linda Runyon is a notable exception to the others, because she isn’t merely an authority on the topic. Rather, she fed herself and her family almost exclusively via foraged and wild foods for many years. She lived the topic and that experience shows in her book. While others focus on plant identification, she focuses on how to use the plant once you know which plant it is. She also provides in-depth nutritional information for many plants. That information may or may not be of interest for hobbyist foragers, but it can be crucial for those who make foraging a major part of their dietary intake.

Another extremely helpful source of information are websites dedicated to foraging information and forager training. One such website is www.foraging.com which provides a mind-boggling array of books, website links and other resources for foragers around the country. You’d have to live a long time to work through all those resources, but wow you’ll have fun in the process. Another website is www.wildmanstevebrill.com, written by a veteran forager named Steve Brill. He is a forager in New York State, who offers books and workshops for those who wish to learn more about foraging. His website provides a lot of different resources. A third website is here written by Laura Martin-Bühler. She also provides a wide variety of suggestions and encouragement for those who are foraging not because they want to, but because they need to feed themselves and their families.

We are so fortunate to live in a society where food is rarely lacking in availability. But many on earth now do not have that luxury, either because of financial hardship and/or geographical distribution problems. If you would like to learn more about foraging, there are resources to do so. If you’d like to add such wild foods to your market crops, there are ways to do that too. I encourage you to at least become aware of the possibilities, whatever your interest.

First Day In The Garden

March 20, 2011

The first day of spring here is usually cold and wet, much like a dog’s nose. You’re always glad to see it but dang you don’t want to get too close to it. So today’s forecast for partly cloudy skies, no rain and temps in the 50’s had us outside most of the day. And glad to be there.

There’s a day in every gardener’s year where you first venture out into the garden after winter’s storms, eager for the new growing season to begin. It is a mellow day for some and a day of grand ceremony for others: The First Day In the Garden. Whether that day happens in January for those lucky souls down south, or February or March for us in this moderate climate, or even as late as April for those pour individuals who must wait until then to see their soil, it’s almost always a good feeling to be back in the garden again. Whatever mistakes made in previous years are behind us, and the growing season stretches out in front of us just bursting with promise.

Our first task was to clean up all the downed branches strewn across the area. With our windstorms in winter, we usually have a fair number of small branches to clean up, along with trash that has blown in from wherever it came from. I had a short scare today thinking that a fairly large branch had possibly damaged one of the beehives which hibernated out in the garden over the winter. Happily, that was not the case. The day was even warm enough that both beehives were actively involved in some housecleaning of their own, so I was able to check them as well. That’s always so nice to see the bees flying for the first time each spring.

Second, we take inventory of what perennials made it through the winter, what didn’t, what might have gone to seed unnoticed the autumn before, and what weeds are already so bold as to be pushing up through the ground and daring us to pull them. Somehow I find it hard to pull weeds on my first trip into the garden. After all, they’re hardy enough to have survived all winter and be first out of the gate in springtime. Surely we should reward that vigor rather than yank it unceremoniously out of the ground. As much as some of you might be shaking your head and thinking “my goodness, what a wimp”, I must say that at least in our garden, the first weeds out of the ground are almost always actually useful plants that have a long history of being early spring tonics, good for the body. Dandelion, chickweed, nettle and nipplewort are all cool-season succulent leafy greens that taste great in salads, and help cleanse the body’s stale blood. So if I pull those out of the ground, it’s usually to eat them and it’s usually done with respect. Never begrudge the plants that grow for free, particularly those that are so good for us.

As for plants which went to seed last year, we had some garlic escape notice and bloom, and their progeny spilled over into one of the walkways. Now that progeny is growing in tight little bundles scattered here and there. I wasn’t counting on so much garlic, but there it is so I’ll make use of it. We have some volunteer radish coming up as well - another stalwart early spring citizen. I never developed much of a taste for radishes until I started growing them for myself. Of course my radishes taste much better than anyone else’s. A common gardener delusion, but I’m okay with that. And I was glad to see that at least some of the rosemary made it through, and of course the chives came through like champs. They don’t mind cold weather in the least. But I lost all my tarragon and thyme, darnit. I’ll have to replace those. And there’s my comfrey poking up spring’s first leaves through the dark earth. I always love comfrey’s gigantic leaves. Chickens love ‘em too.

While we have other productive areas of the farm, somehow the garden is different. We don’t grow for market here anymore. Whatever is growing here is for us. So we can grow things here that we’ll never sell, and which have no purpose other than we like it and we want it and we had a place for it. So my wild clover patch is here, and my wrought iron rooster planter which always tips over (but I love it anyway), and the lemon balm which I bought on a whim and now can’t live without. The mints and horseradish impatiently live here, chafing at the confines of their pots, yearning for the chance to take over the world. I’m even growing out a few hazelnut seedlings from last year, and the strawberries that I bought at a flea-market of all places but which put out the most amazing berries. This year we’ll be planting some new things out here - we’re finally building dedicated beds for asparagus and rhubarb, and I want a dedicated medicinal herbs area. So many plans for the garden and it’s only barely springtime. But dreams grow well in spring just like the garlic does. May a lot of those dreams thrive in the coming year, just like the garlic. And maybe a few of those dreams will go to seed and spill some progeny of their own, to sprout and root and grow while no one is looking. What a nice thought.

Good Dirt

March 18, 2011

We’ve been doing a tremendous amount of planting and transplanting in the greenhouse lately - peppers, rosemary, thyme, tomatoes, sage, oregano. So much transplanting that it seems I’ve never had hands or clothes without soil stains on them. So it might seem odd that I would come home, wash up, and then turn around and write about soil. Yet, soil is at the core of everything we do. There’s the saying that if we don’t have our health, we have nothing at all. It could just as easily be said that if we don’t have good soil, we can’t have good health. Why is that?

We live in an unprecedented time, when people have become accustomed to empty calories. We instead pop pills to maintain our health. Whether those pills are pharmaceutical or natural in origin, they still indicate a fundamental lack of adequate nutrition in the foods we eat, which in turn indicates a lack of adequate nutrition in the soil. How have we come to this place? By forgetting that good nutrition comes from the soil. If the soils are unhealthy or devoid of nutrients, our foods will be too. And if our foods are devoid of nutrients, our health cannot be long maintained.

So how do we make and keep the soil healthy? It’s easy to think that soil fertility is simply a question of dumping enough fertilizer on the fields. Many farmers and gardeners are very well acquainted with the big three nutrients required by plants: nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium. Those three elements are so important to plant health that the ratios of N:P:K are listed on every bag of fertilizer sold in this country. If you’ve ever wondered what it means when you see 5-10-5 or 2-14-6 or 12-2-2 listed at the bottom of a fertilizer bag, that is the N:P:K ratio contained in that particular product. But soil fertility, and the resulting nutritional value of the plants and animals grown on that soil, goes way beyond those mere three elements.

While those three ingredients are definitely needed by plants, there is another group of nutrients called the macro-nutrients, which include calcium, magnesium and sulfur. These nutrients are not required in such great amounts as N, P or K, but they are crucial for plant health, and for our health. Poor calcium levels are of course tied to osteoporosis, but if the soils are lacking in calcium, so are the dairy products produced by dairy animals raised on that land. Micronutrients include chlorine, iron, boron, manganese, zinc, copper, molybdenum and nickel. These are required in even smaller amounts, but are again crucial for proper nutrition either in plants, or the creatures that consume the plants. Nutritional deficiencies in any of those will have repercussions in health. And finally are the trace elements such as selenium, iodine, fluorine, cobalt and chromium. Even gold is considered a trace element for some plants, and they don't do well if deprived of it. If we rely on those plants, we won't do well either.

While all this might be fascinating, what relevance does it have for the home gardener or market grower? Plenty. More and more information is mounting from both the research realm and anecdotal experience, which says that soils which are deficient in certain elements will create health problems either in the plants that grow there, and/or in the animals and people who eat them. For instance, many soils in the USA are deficient in selenium, iron and/or copper. These are not generally included in any fertilizer currently available on the market, because they are needed in such small amounts. Yet a lack of iron leads to anemia in adults, and slower learning in children. A lack of copper has also been associated with learning difficulties. A region of the USA deficient in iodine has become known as the goiter belt. Where the soil is deficient in selenium, livestock are prone to being born with white muscle disease, which is a generalized failure of the musculo-skeletal system resulting in loss of strength. Chromium and/or vanadium are involved in the passage of insulin across the cell membrane amongst at least some mammals. If we don't add those elements to the soil, we won't have them in our foods and in our bodies.

Even when we do add them to our soils, the situation gets more complicated. Elements do not act independently of each other. Too much of one can either accelerate or interfere with the absorption of another. So not only do all the elements need to be present in the soils for optimum health, they need to be present in the correct ratios. And finally, as if we didn’t have enough to think about already, those soil concentrations also depend at any given time upon things like temperature, pH, oxygenization and water content of the soils.

So how do we ensure that our soils are made fertile and kept that way? Thousands of pages have already been written about soil health, and I certainly can’t best all those efforts in this brief little blog entry. But I can provide the titles for some good introduction books on soil health and soil fertility:

The Soul of Soil: A Soil-Building Guide for Master Gardeners and Farmers

How to Have a Green Thumb Without an Aching Back: A New Method of Mulch Gardening

Healthy Soils for Sustainable Gardens (Brooklyn Botanic Garden All-Region Guide)

Teaming with Microbes: The Organic Gardener's Guide to the Soil Food Web, Revised Edition

Most of the above books are written for gardeners, rather than farmers, and most of them only address how to get the elements into the soil, rather than the nutritional value of the elements for our foods. Why is that? There are certainly soil science books written for farmers, and nutritional books written for chemists, available through Amazon.com or even your nearest university bookstore. But they tend to run towards the expensive end of the scale, and they often assume you’ve already had your Chemistry 101 and Physics 101 classes. Additionally, the newer soil books address artificial fertilizer use and large-scale delivery systems which are only applicable to growers working at that scale. The newer nutritional books may or may not address natural sources for this-or-that nutrient, but they will almost certainly not address the issue of soil fertility or lack thereof. The above books, on the other hand, are much more affordable, give you a very good understanding about what’s going on in the soil and in the plant, regardless of whether you have a single planting bed or 10,000 acres of wheat. You also don't need advanced science degrees to understand them. And best of all, these books focus on low-cost, low-impact, diversified ways to build robust soil fertility. All in all, reading these books will give you, Dear Reader, a much better understanding of whatever soils you’re working with, and how to improve them, regardless of scale. Improving the soils will then improve the plants you grow there. Improved plant health will very nicely improve your health as well.

I cannot claim to do every last thing recommended in every one of these books. But each year we’re doing more and more of them. Working to build and maintain fertile soil is perhaps one of the highest priorities on the farm, or in the garden, for anyone living from the fruits of their labor. So tomorrow I’ll go right back to my planting, and transplanting, and getting my hands and clothes dirty. And be very thankful for all that good dirt.

Why I Don't Hate Eggplant Anymore

March 16, 2011

I have a confession. I despise eggplant. I had it a few times as a child, cooked into this or that dish, and I decided very quickly that this was not destined to be one of my favorite fruits. But I didn't stop there. I developed a hatred for this poor undeserving creature, and I dreaded the news from my mom that we would be dining upon it yet again. We didn't have it very often, but I remember thinking we could wait 100 years before having it again and that would be just fine with me. Finally, things came to a head when Mom decided that we were going to have a baked eggplant for dinner one night and both my brother and I thought "ew, not again". But something was wrong with that particular eggplant. It exploded in the oven while baking, coating the inside of the oven with a thick paste of half-baked eggplant goo. Of course we weren't home at the time so that goo was left to cook onto the oven walls. The smell in the house was incredible. We got home, discovered the accident, and Mom promptly started muttering about so much for that dinner. My brother and I didn't dare cheer in her presence, but we were quite relieved. That was the last time eggplant was ever served in our house.

Fast forward several decades, and my opinion of eggplant has mysteriously changed. I've warmed up to this big purple fruit, and not because I like the taste any better. Rather, I like to see those little eggplant starts growing in the greenhouse, putting out their characteristic big round leaves, looking for sunshine. When I look at them in their little seedling trays, I don't see eggplant casserole anymore. I see dollar signs. Those little starts sell quite well at market, and they grow well here. My partner has reported that she generally sells out of eggplant pretty early in the season, so they're one of her gotta-plant items first thing in the year.

Farming is defnitely about growing things that we enjoy. And for most folks, if they enjoy growing one type of plant or animal, it usually doesn't take much additional enthusiasm to grow other types of plant or animal (or both). So expanding our operations to grow a lot of different things is rather natural. If we're gardening or farming or raising livestock for our own purposes, that's usually the end of the selection process. Unfortunately, if we're trying to sell to market, that's only a part of the equation. The marketplace has as much to say about what we raise, grow and sell, as we do. Suddenly, personal preferences are no longer the only criteria.

I've had a number of people ask me what they should raise or grow when starting a farm. I usually give a two-way answer - "what do you want to raise, and what is your market?" Unfortunately, many wanna-be profitable growers and livestock owners don't look at what the market wants. They only look at what they like. Hence the flood of zucchini in August. If folks want to make decent income at this lifestyle, they need to know what their customers want even if they don't particularly enjoy it themselves.

It doesn't have to be misery for the farmer though. Folks can find a way to sell items they would never raise for themselves, or market products to the public in ways that are very tolerable. I remember one such instance where I attended a nutritional workshop for small ruminants. The speaker was extremely knowledgeable about sheep in particular, and how to raise feeds specifically for them. He'd talk with an obvious depth of experience about what they'll graze, what they won't, how quickly they'll browse through this-or-that type of pasture, etc. He would often refer to the sheep as "the little darlings" with a British accent that led me to think he absolutely loved his sheep. No wonder he had such a depth of knowledge. After the workshop, I thanked him for that presentation and told him his own flock must be very lucky to have such a knowledgeable owner. He laughed and said he'd sold his flock years ago. "Got so tired of the lambing and the banding and the shearing and the pasture maintenance, it just got to be too much. So I finally sold them all. Now I just talk about how to feed them, and that's enough for me." At first that comment really shocked me, and some how cheapened the knowledge which only moments before I had found so impressive. But thinking about it later, I realized that he'd been able to find a comfortable way to earn a decent living using knowledge that he had gained over many years, without doing work that he had come to find wearisome. I certainly won't be mailing him any lambs for his birthday. But that impressed upon me how important it is to identify alternate markets where we can provide either products or services, to the benefit of both buyer and seller. He'd found his niche and he was very good at it. The fact that he no longer wanted to raise sheep was a non-issue for his ability to continue to make a living with sheep.

So to the eggplant growing in the greenhouse, I can smile warmly at them every day between now and whenever they sell. I can water them and transplant them and tend them lovingly, knowing I can raise them well without ever having to dine upon eggplant again. Know your market, Dear Reader, and know what they want. If they want something you can provide, I'll bet there's a way to provide it even if you don't personally like it very much.

Four Alarm Fires

And Other Learning Curves

March 14, 2011

I had the privilege and pleasure today of helping someone hopefully save a life. Not a human life, but an animal's life. Maybe not quite as high on the "wow" scale as saving a human life, but even so it was a privilege. Perhaps the best part was that by doing so, a few more people learned a few more tidbits about how to keep livestock "live".

It all start with a young, inexperienced goat owner who posted to one of the livestock groups last week, that she thought her buck might be sick. He was off his feed, moping around and not really socializing much. All three of those would be great big alarms in the minds of most livestock owners. The question was - what to do about it? This particular livestock list explores ways to manage livestock health with a variety of holistic methods, rather than merely reaching for the bottle of antibiotics. And to be sure, there are MANY ways to manage animals without resorting to antibiotics for the vast majority of health issues. While talking about some of those methods goes well beyond the scope of a single blog entry, that's not really what I wanted to talk about today. Rather, the learning curve that every livestock owner needs to figure out, at some point, to determine when a health issue is a minor problem, versus when it's a four alarm fire. The cues are not always obvious, and the window of opportunity is all too often pretty small. In this case, it was a close call.

The goat had first seemed "off" several days prior, and the owner had kept an eye on him over the weekend. During that time, his normal diet had gone from a wide variety of browse items along with hay and supplements, down to just browse and hay, down to just browse alone. His social interactions had decreased, and his body language had grown increasingly worse - head hanging down, lethargic, aware of his surroundings but not really paying attention in a goat's normally relaxed but alert way. So the owner had tried to encourage him to eat more via hand-feeding, to less and less avail. She had sought advice early on, and had gotten recommendations to try this-and-that supplement, herb or other natural product. Then he started showing some discharge from one nostril. Several of us said "OK, this is getting more involved, take his temp and let us know." This morning it was 103F, which is borderline high for a normal goat. This afternoon, it had jumped to 103.8F. Every alarm bell in my head starting ringing real loud. Several of us sent urgent emails to the owner saying "OK, this is a very sick animal, we can't take our time anymore with this-and-that general immune boosting food, we need to give him stronger medication and we need to do it ASAP. He's fighting for his life and that battle will be decided in the next 12 hours, depending on what you do now." Several of us gave her specific drug dosages and intervals, along with supportive care information to help him get over this crisis and live to see tomorrow. As I have written in previous blogs, she didn't have any veterinarians in the area who would do farm visits. So whatever methods would be used to save this animal's life would be hers to do in the overnight hours. There was no one else to call.

That "moment of truth" is something a lot of livestock owners face, for a variety of reasons, and it can be quite intimidating. How do you ask an animal what's wrong? How do you sort out all the different options, and figure out the most likely cause of trouble? And once you've figured out that much (and there's no guarantee you'll even get that far), how do you kow what to do? The answer to all three is a combination of experience, preparation, observation, and risk assessment. This owner has three of those, but she was missing the fourth. That's where the rest of us stepped in.

Most livestock owners can instantly tell when someone doesn't feel well. They act different and that sticks out like a sore thumb when you watch your animals every day. This owner had that experience a-plenty and she knew something was wrong. She had prepared for emergencies by putting together a decent first-aid medicine cabinet stocked with things like syringes, antibiotics, electrolytes, probiotics, etc, so that was ready to go. And she had kept this animal under close observation for several days, such that his pattern of decline was clearly documented and reported. What she couldn't see, which we could see, was how serious this was, how quickly the situation was deteriorating, and at what point she needed to pull out all the stops to help the animal get over the illness. That last part, sadly, comes from going through it a few times and seeing various end results (sometimes happy, sometimes not so much). That's where we came in. But it's not magic - it's a procedural evaluation of that animal's health that anyone can learn. And tonight, she's a little farther along that learning curve thanks to several individuals who helped guide her during some crucial moments.

I don't know if the goat will live. But I do know that she has now given him his very best fighting chance to get over this illness and recover. That's usually the best (and most) we can do. As for the learning curve, these conversations happen so often, on so many lists, that it's becoming rather familiar to step someone through all the diagnostics to identify what's wrong, determine a course of treatment, and make quick decisions about how best to proceed. My livestock mentor and I have started doing this so frequently that we'll be putting together a whole new section on disease prevention, detection and treatment intended for livestock owners just like the gal I helped today. Only by teaching these evaluation and treatment methods will today's livestock owners be able to adequately address even garden-variety health issues in their flocks and herds. It's another gotta-do item on typically already long gotta-do lists, but it's a valuable skill. Particularly in the middle of the night during a four-alarm health crisis, when there's no one else to call.

A Whirlwind Tour Through

Season Extenders

March 12, 2011

My farming partner and I have been working the last few weeks in her several greenhouses, planting and transplanting the first crops of the year. Amongst those crops are peppers, tomatoes, eggplant, lettuces and cool-season salad greens. We've also gotten some herb cuttings going including rosemary, thyme, sage, tarragon and mints. Our work has primarily been done inside because the weather outside has been dreadful, particularly this year. We’ve had rain almost every day for the last two weeks. Not the warm, gentle rains of a warm spring, but the cold, bone-chilling, blustery rains of a winter that won’t let go. We may be listed in the USDA’s Zone 8, but the Pacific makes sure we don’t warm up very fast in springtime. In fact our spring doesn’t generally yield to summer until around the second week of July.

Given that climate, most producers here use a variety of season extenders not only to provide protection to tender young plants, but also provide protection to grouchy farmhands (such as myself) who absolutely hate working in the rain. Ok, I’m a wimp, but I’ll work inside on nasty days if at all possible. The nice thing about greenhouses and hoophouses is they give us the ability to get work done on the farm, regardless of the weather. And I can safely say that if I dislike working in the cold rains of early spring, you can bet our seedlings don’t like it either. Yet if we waited for the weather to warm up and stabilize, we would have missed half our growing season. So there’s a genuine economic benefit to having those season extenders.

But what type of season protection do we need? Ahhh, that’s really the million dollar question that most producers have asked, and asked again, over the years. The answers keeps changing. Not because the plants want different conditions, but because the options keep increasing. Starting from simplest/cheapest to most expensive, here’s a rundown of the most common season extenders in use on our two farms and in our area:

Floating Row Covers

Floating Row Covers are the cheapest, simplest form of season extension. They consist of a thin woven film of manmade material, which is permeable to air, water and sunlight. One very common form of floating row cover is a product called Reemay. Row covers are intended to provide minimal protection to tender plantings from the worst of wind, rain and chill, but they are not intended to protect plantings from actual storm conditions. One nice feature of such covers is their light weight - they are so light that even emerging seedlings and delicate leafy greens won’t be crushed underneath it. We use Reemay when we harden off our lettuces for the first few days, particularly this time of year. Even nice days this time of year tend to be breezy with scattered cloud cover, resulting in warm sunbreaks but chilly cloudbreaks. An interesting side benefit of Reemay is that it can hide even mature crops from various pest insects which would otherwise fly over and land on the plants. It isn’t 100% protection, but it has provided considerable protection for plants which otherwise would likely have been decimated by such pests. A caution is warranted, however, because Reemay can also trap insects which are emerging from the soil, such that they are required to feast on the plants under cover. So, know your pest and how it attacks plants before you rely on this for protection. And if you use it for mild weather protection, either be ready to bring in those plants if wind and rain move in, or weight down the cover with bricks, rocks or soil. Otherwise it will blow away and decorate the nearest trees.

Heat Mats and Germination Chambers

Heating mats are commonly used with a variety of indoor propagation methods, but not so commonly used outside. Just as the name implies, they are rubber or plastic mats which heat up to provide root-zone heat. Some of the more expensive ones can be plugged into each other and/or into a thermostat which allows the grower to literally dial in the desired temperature. Some of them need protection from water, and others are waterproof. All of them can provide a real jump on germination times by putting the heat right where it’s needed - in the soil. I have worked in unheated greenhouses where the air temps were near freezing but the seedlings were perfectly happy, because their root zones were a steady 60F or 70F or even 80F. If you’re working with tender young plants, nothing smooths out the rough edges to early spring quite like warm roots. Germination chambers take that even further, by providing not only root zone heat but also dramatically boosted air temps in a small area around seedlings, just long enough to get them started. One of our region’s growers has really mastered this method. He created rolling germination chambers made from tall commercial bakery-style racks, covered with a shell of tacked-on or taped-on greenhouse film. The rack holds multiple shelves of seedlings. Each shelf held something like three or four standard seedling trays, and there was only a few inches’ clearance between the top of one tray and the bottom of the next. But that’s all he needed. In the bottom of the rack assembly, he has a reservoir of heated water that provides gentle moist heat to the whole thing, and dramatically reduced the need to water the trays. He had figured out the planting dates and germination times for a wide variety of crops, including some crops that are not normally started in this fashion, such as sweet corn. He has about a half dozen of these racks in an unheated greenhouse, along one wall, constantly rotating new trays in and seedling trays out. That small area is the work horse for his early-season planting activities, and a profoundly efficient use of space, heat, electricity and irrigation.

Cold Frames and Hot Frames

Cold Frames and Hot Frames are older, tried-and-true ways to improve germination and early-season or late-season production, but without the need for a larger hoophouse or greenhouse. These frames are generally built over planting beds, and are several feet tall, several feet wide, and as long as needed (sometimes covering the entire planting row or planting bed). Older farming books will talk about frames made of wood and glass. Newer books and a tour along modern farms will see greenhouse film and PVC hoops used instead. Either way, this approach is only intended to provide mild to moderate protection to the actual plant in the ground, rather than seedlings in trays. The frames are not tall enough for people to walk in. Cold frames have no heat source other than sunlight, but even that can provide sufficient heat that the covers will need to be lifted or removed on sunny days. Frames also allow the soil to warm up faster than usual, not only because of the heated space but because cold rains are kept off the soils. Moisture contributes greatly to soil temp - the drier the soil, the warmer it is. So between the drier conditions and the storage of solar heat, the temps experienced by the plant can be considerably warmer than they would be otherwise. Hot frames have the same general construction, with one major difference - soil heat is provided. That soil heat was traditionally provided by burying fresh horse manure in an excavated hole or trench to a depth of 8-10”, then covered with regular soil, then covered by the frame. The manure’s decomposition would heat the soil above it, giving steady gentle heat for up to about 8 weeks. Once that source of heat had been used up, the seedlings were generally far enough along that they no longer needed that additional heat. The nice bonus for that approach was that the now-rotted manure provided a nice nutrient source for the growing roots, thereby providing not one but two services to the growing plants. The manure portion of this approach has been replaced over the years with heating cables, heating pipe, and then finally with the heat mats described above. But somehow I suspect the plants all enjoyed that compost.

Walk-In Hoophouses

Walk-in hoophouses were probably an expansion of the cold frame concept. A 24” tall cold frame would protect the plants, while a 72” hoophouse made of the same materials would protect both the plants and the farm workers. Given that most hoophouses use bows or arches of wood, metal or PVC, going taller also generally meant going wider. So those taller hoophouses could therefore cover two or three rows or beds instead of just one. That meant a greater working area with better working conditions. It also meant a larger contained air volume which dramatically slowed down the temperature swings overnight. Hoophouses can definitely still drop below freezing in sharply cold, or extended cool weather. They can also definitely overheat in sunny weather. In fact, they can only functionally be about 50’ long without having the ability to raise the sides. That’s because a hoophouse longer than 50’ will rarely have enough air movement to adequately ventilate the middle of the house, even if both ends are open. Raising the sides can alleviate that problem and allow the houses to be as long as desired.

Greenhouses

Greenhouses differ from hoophouses in terms of size, permanent versus temporary construction methods, and usually the inclusion of electricity, plumbing and some form of automatic ventilation. Because of those additional features, greenhouses often have permanent flooring, dedicated beds, and/or other infrastructure to maximize the efficiency of whatever is grown inside. I can’t give too many more details about greenhouses, because the details vary so much according to whatever is grown inside. But they generally require an order of magnitude more money to build, along with permits and inspections during construction because they are permanent structures. Still, the additional infrastructure can make a nice difference if the farm is ready to pay for that additional efficiency.

So if you are despairing of the weather, Dear Reader, and wish there was a way to get going with your planting a little earlier, or keep working in the dirt a little later, one or more of these methods can definitely serve you well. Consider your goals, your circumstances, your climate and your pocketbook, so that whatever you choose fits you, and your operation, comfortably.

Mo' Info, Mo' Betta'

March 10, 2011

Me as a young(er) goat owner, feeding

bread to our first three goats

It occurred to me after writing my previous blog entry that it’s not enough to merely say “there is a lot of information out there to help farmers run their farms more profitably.” That’s a general statement and without specific examples, it’s relatively worthless. So, today’s blog is devoted to listing and describing the sources of information that we’ve used in our own farm development efforts, and/or organizations who have helped farmers graduate from merely producing things to producing things profitably. This latter category is aimed at young and beginning farmers, but it is also applicable to anyone who has been running a small farm as a hobby effort, who is ready to move into profitable operations.

In our farm’s case, we have gotten most of our information from one of two sources: our county-level Extension Service and Conservation District offices. The former is a national network of offices, generally at the county level, and generally associated with that state’s agricultural university. For instance, our closest Extension office is WSU-Snohomish County Extension. We are not limited to the nearest office. Neighboring counties will often collaborate and share their resources, staff, and workshop schedules. We have attended workshops hosted by Thurston, Pierce, King and Skagit counties’ Extension offices. Our county’s livestock advisor program is coordinated by a staff member from the Skagit office, and many of the workshops hosted in one county will draw volunteers and attendees from surrounding areas. The Conservation District offices are set up in a similar way, but are not tied quite so closely to the land grant University system. Their funding sources are different, and their mandate is a little closer to resource protection and resource management. But they still work very closely with producers at all levels, as well as with local, state and national agencies. Boundaries between the two agencies can occasionally blur. But one stated mission of the Conservation District is to offer all their services in a non-regulatory-enforcement way. That means, if I know I probably have a manure pile that is leaching pollutants into a nearby stream, I can call the Conservation District about that and ask them to help me figure out how to design, permit, build and maintain a cost-effective, long-term solution. All without them starting or ending the conversation with “and we’re going to have to report this to the appropriate agency and you’re going to have to fork over $$$$ in penalties….” They are very motivated to help land owners and farmers to avoid or remedy compliance problems, rather than bust them for compliance problems. I should also say that the vast majority of services provided by both agencies are free to the farmer. Some workshops will have an attendance fee to cover the cost of handouts, refreshments, facility usage, etc. But the economic value of that free consulting has been beyond measure, at least for us.

To give an example of how the Extension Office and Conservation District work hand in hand for producers, consider one recent example. We are planning to license our farm as a Grade A dairy at some point in the future. Since we have no previous dairy experience or infrastructure on our farm, we’re starting from scratch. So we have been consulting with the Extension Office personnel regarding the business planning, food safety, marketing and regulatory requirements portions of that project. We have been consulting with the Conservation District to develop adequate, cost effective (and in our case, surprisingly low-tech) wastewater handing, manure handling and water quality protection strategies. Thanks to those services, we have tentatively designed an on-farm facility which we already know will be in compliance not only with national milk production requirements, but also will ensure no soil, air or water pollution issues for us, our neighbors, or anyone downstream. It has been a wonderful advantage to work all that out in advance, on paper, with consulting experts, rather than figure it out after the concrete has already been poured.

Those are just two of the agencies we’ve used over time. A third favorite of mine is ATTRA.org. The massive ATTRA website is a repository of hundreds (if not thousands) of articles and reports on just about every conceivable agricultural operation. Each article and report provides an overview of the issues, challenges, opportunities, regulations and economic considerations for that farming activity. These reports typically provide several case studies of growers who have already tried this approach, and what their results were. Additionally, and perhaps most importantly, each report provides a lengthy section devoted to Additional Resources - websites, research facilities, reports, books, etc. We frequently reference the ATTRA website when we want either a quick rundown of a given new topic, or more in-depth information on something. In the past year, we’ve researched the following through ATTRA:

On-farm Composting Methods

Marketing and Business differences between CSA’s and Farmers’ Markets

Cover Crops Management

Small Grains Production

Pastured Poultry

Greenhouse and Hoophouse Design, Construction and Management

Microdairies

On-Farm Commercial Kitchens

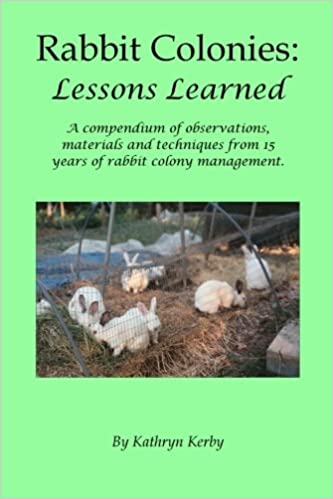

On-Farm Rabbit Processing

A third category of assistance is a relatively new development, but it’s something that I have found very encouraging. Namely, the springing-up of countless New Farmer/Young Farmer websites and support organizations around the country. These groups were not around when we first got started, and I wish they had been. But now there seem to be dozens of such groups all with the mission to provide support, mentoring, networking and logistical assistance to either young and/or beginning farmers. Some of these groups are offshoots of existing groups. For instance, our local Sno-Valley Tilth group has a new farmer mentoring program which I believe is only in its second or third year. Our region’s Cascade Harvest Coalition also has something called Farmlink, which is an attempt to pair up young landless producers with older landowners who are either retiring, selling their property, or simply wanting help to work their farms. But there are a variety of regional and national groups dedicated to helping this next generation get started either with work experience, and/or with actual farm business planning, design, execution and on-going management guidance. Here is a partial list of such organizations:

National Young Farmers Coalition

Oregon State University's Beginning Farmers page

BeginningFarmers.org

Farmlink.org

National Agricultural Library article on new farmer resources

New England Small Farm Institute’s New Farmers resource section

Washington State's Young Farmers website

Cornell University's Beginning Farmers program

If there is a single mistake that struggling farmers are making now, it’s denying themselves all the how-to information that is available through such agencies and organizations. Whether they are just started out, need minor tweaks to an existing operation, or want to completely revamp the farm, that how-to information is out there. Even simple Google or Youtube searches will often yield impressive information on any given aspect of, or activity in, modern agriculture. For anyone who has said “gee, I wish I could figure out how to do X”, the answer is as near as your nearest internet access. There’s more information out there now than ever before, on how to farm, farm well, farm profitably and farm in ways that provide and protect a wonderful quality of life. But it’s up to each of us to go get that information and make use of it. I sincerely hope a lot of folks choose to do so.

Great Expectations

March 8, 2011

I have heard it said, far too many times, that farming is the art of buying at retail and selling at wholesale. I have also heard it said that the best way to earn $1 million in farming is to start with $10 million. More succinctly, it all boils down to a lament that drives me crazy because I hear it so often: “there’s no money in farming.” Know what I say? “Hogwash.”

Farming is many things - a lifestyle, a hobby, a passion, a career, a passing fancy. It can be all those things, and do very well at any of those scales of operation. But it can also be a business, run with the same philosophies, conceptual tools, planning methods, and decision criteria as any other business. The owner is ultimately the one who decides whether it will be a lifestyle, a hobby, a passion, a career, a passing fancy, and/or a business. The trick is, many farm owners don’t look at it that way. For whatever combination of reasons, the “business” portion is often ignored, avoided, neglected and/or denied. Even more oddly, some farmers react with distaste if anyone mentions the word “profit” in connection with their operation, as if that word was either unknown, unwanted, or otherwise unwelcome. Which is the beginning of the end of most farming operations.

If someone were to open a small grocery store or hobby store or bookstore or dentist’s clinic, they’d have the same market opportunities and challenges in front of them that a small family farm faces. Yes many details would be different - the regulatory landscape, the marketing niches and competition, public perceptions about what constitutes good food and good pricing. But the vast majority of the principles would be the same - know your market, know your competition, know your regulatory requirements, know your operating costs and for goodness’ sake, know your break-even points. But for some reason, the individuals who open the small grocery store, hobby store, bookstore or dentist’s clinic are all implicitly expected or even explicitly pressured to make a profit as part of whatever other community service and/or business goals they have. Yet farming is almost universally expected to lose money. That is a disease not of the business itself, but of the owner’s expectations and the public’s perceptions. No more, no less.

On the one hand, there’s probably a number of ways to turn that around. There are workshops and books and conferences and advisors and advocacy groups and marketing cooperatives galore, each with the goal of helping farmers make a decent living, stay on the land and keep that land productive. More recently, that productivity aspect of things has been further refined to meet “the Three E’s”: ethical, environmental and economic standards which help ensure not only short-term survival for the business but also long-term health for the community. All of that effort and support is marvelous, but for one big screaming weakness: farm owners need to be willing to make use of those resources AND put into practice what they've learned. Many farmers I know don’t make good use of those resources, for a variety of reasons. Sadly, even those that do often fail to put those methods into practice. If you ask them why they didn’t follow through, you’ll hear a lot of reasons. But fundamentally, I think it boils down to only three things: "it won’t work for me", "it doesn’t apply to me", "I can’t do whatever is needed to get it done". And so farmers continue to flounder.

Yet applying some creativity to that same situation can yield some impressive results. A third- or fourth- generation farming family in our own area was in danger of closing down. The husband and wife team had raised their kids on the farm, then watched them grow up and move away. Their particular type of farming had gotten too full of regulatory hoops for their taste, and making a profit had eroded down to squeezing the operation for every last precious penny. They were worn out, fed up, and nearing retirement age. None of their traditional farming strategies worked anymore. They were done. Meanwhile, one of their grown children had silently been mulling a return to the farm. He was married with kids of his own, and his big-city career no longer provided the quality of life he wanted for himself or his family. When his folks decided to get out of farming, he used that opportunity to get into farming. But to his credit, he completely re-invented his parents’ farm. He dropped the commodities production, he looked at modern market options and marketing strategies, and he brought his Corporate America business lessons with him regarding customer service, product diversity, pricing, competitiveness and a whole host of other skills which he had learned simply by being an adult in the business world. He turned that farm around within the space of a few years, and is now considered so successful that he teaches new farmers how to succeed at farming. The lesson here was that he looked at what was working, what wasn’t working, what he wanted, what he needed, and how to get it. He was not chained to methods or products which no longer made sense. That willingness to try new things, in an educated, carefully planned way, allowed him to succeed where the exact same farm in the exact same family had been on the brink of failure.

There is absolutely no reason why anyone and everyone else who wants to farm, should fail to make a decent living at it. Many, many resources exist to help new and existing farmers figure out how to not only live the life they want, do the work they want and sell the products they want, but also make the money they want. The only thing standing in our way is our own expectations. If we expect to lose money, we’ll probably find a way to do so. If we expect we’ll need to put in some time and effort to create a successful business, and then carry through with that plan, we’ll be in excellent shape to do exactly that.

Veterinary Deserts

March 6, 2011

Back in January I wrote about an adventure with a cow that resulted in us calling for veterinary assistance. Thankfully, the vet arrived and the crisis was averted and we had a happy ending. But that day also taught us something important, and altogether disquieting. Namely, that veterinary support is no longer a guaranteed thing for livestock owners, even when veterinary facilities are only a few miles away. Veterinary coverage of non-equine livestock has become something of a sore point for veterinarians, for a variety of reasons, as I elaborated in a subsequent blog entry here. Yet, the need for skilled healthcare support still exists. Since then, I have been researching options which will not only help fill that gap, but possibly render it not nearly so important. Furthermore, those options need to be relatively easily shared amongst all sorts of livestock owners - locally, nationally and internationally. Yes, that’s a big task. Yes, it is undoubtedly complicated beyond my mortal ability to measure. But the need is there. If necessity is the mother of invention, then let’s invent something that is really, really helpful to as many people as possible.

I should also say here that this effort is in no way an attempt to declare veterinary medicine as either simple or easily taught or, perish the thought, irrelevant. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Good veterinarians are priceless. But the reality is that they are fewer and farther between, with each passing day. Our efforts only aim to supplement that profession, where members of that profession are not available.

Towards that end, I have been talking to a wide variety of other livestock owners about how best to tackle this issue. The task at hand - how to replace primary veterinary support for livestock health issues, breaks down into four general categories:

1) illnesses which can be either avoided with sound management, and/or typically treated by owners with timely application of non-prescription materials. Examples of these illnesses would be issues such as ketosis, hypocalcemia, enterotoxemia, coccidiosis and white muscle disease.

2) Nutritional consultation to build healthy herds that are more resistant to environmental stressors

3) Injury assessment, stabilization and/or treatment

4) Completion of standard livestock procedures to minimize the need for veterinary involvement or intervention. Examples would be pregnancy detection and management, difficult birthing management, disbudding, banding, hoof trimming, castrating, vaccinations and tattooing.

A parallel development has emerged while researching the above four categories. Namely, most communities and rural areas have a population of skilled professionals who are not licensed veterinarians, but who do have credentials within the medical/veterinary fields. These professionals often have skills, experience, techniques and/or equipment which can all be used to assist during various individual animal health events and/or herd management. Examples would be licensed and/or retired veterinary technicians, human medical professionals, high school, community college and university instructors and research staff, 4H/FFA leaders and even other livestock owners within the farming community, who can contribute to ongoing animal health care.

I’m not the only one asking these questions. In my research, others have echoed the lack of veterinary care in their particular areas, the concerns that they will not be able to find medical help when needed, and the questions about how to provide that care themselves. My livestock mentor has fielded questions from concerned goat owners for many years, sometimes taking several calls a day from as far away as Ireland Ethiopia. She and I both participate in on-line forums for livestock health and management, which includes both emergency and non-emergency requests for assistance. She and I have talked extensively about this shortage of veterinary support, and have come up with a few preliminary ideas:

1) provide diagnostics information online, so that owners can more easily determine what is wrong with ailing animals, and what their treatment options are

2) provide a variety of workshops and seminars to teach owners a variety of hands-on methods for dealing with common health issues and/or management techniques, such as delivery assistance, first aid and disease treatment, and emergency first-aid.

3) Build and maintain a network of health field professionals who can be consulted for medical questions which span species. These specialists can then be included in on-going owner training sessions, and/or serve in an on-call basis.

4) Launch a seasonal newsletter for livestock owners to address common health and management issues, and point them towards sources for training and support.

My livestock mentor and I have only started to work on any of the above issues. I have no doubt other livestock owners and groups are also working on building similar support systems. Regardless of who’s doing the work, the end result will be the same: the bulk of the effort will ultimately come from……you guessed it……..the owner. Livestock owners will no longer simply be able to pick up the phone whenever something goes wrong with their animals. Ironically, it has never been easier for owners to get the information they need, thanks to the Internet and the many social networking options available now. We absolutely have our work cut out for us but thankfully the tools are largely in place to accomplish that work. Best of all, the result will be livestock owners who are better equipped, better trained and better able to manage the health of their flocks, like never before. It is a new age for livestock owners. Both the effort required, and the resulting benefits, are great. May we all take this responsibility and opportunity to heart.

Happy Seedlings

March 4, 2011

As our planting season gets underway, there’s always the question of how best to prepare those wee little seedlings for the big wide world. And there are as many theories about how best to do that, as there are gardeners and farmers fussing over seeds. I have tried a few methods, many of which I didn’t like because they didn’t work for me. Not that they were stingy, per se, but because they were a poor match for my particular growing conditions. A few I’ve either tried or seen other folks use, which did work for me and/or for them, have subsequently been used year after year with good results. I thought now would be a good time to share some of those lessons.

First, in the category of “stuff that doesn’t work”, the top of the list was my Great Tomato Experiment from a number of years ago. I wanted to get a head start on my largest planting yet of tomatoes - 400 plants. Since I didn’t have access to a greenhouse or even a hotframe at that time, I converted my office into a mini-seedling room. I put up lights and set up tables to house all 400 of those little plants. I also didn’t want to mess around with transplanting them, so I potted everything up in those small formed peat pots, which can go directly into the soil. It was a beautiful thing to behold, row after row of those little cups, each holding a small tomato seed. More precisely, it was a beautiful sight until things started to go wrong.