|

Search this site for keywords or topics..... | ||

Custom Search

| ||

Livestock Guardian Dogs Guide

Our beloved Sam, escorting a goat kid who is only a few days old. Sam came to us as a rescued LGD through the National Anatolian Shepherd Rescue Network (NASRN) as a 9 year old dog. Despite being a senior dog, he taught us an immeasurable amount about how amazing these dogs can be. We lost him as a 13 year old in 2009, shortly after this photo was taken. He worked right up to the end. We still miss you, Sam.

A Crash Course In The Realities Of Life

With An LGD

Have you thought about getting a livestock guardian dog for your small

farm or ranch, but you weren't sure if it would work out? Have you

admired these dog breeds and wondered if they would be suitable for a

suburban or urban home without livestock? If you have ever thought about

adopting or buying a livestock guardian dog for any reason, this page

is for you.

We have received countless questions over the years, about the pro's and

con's of livestock guardian dogs. And there are definitely pro's and

con's. This page was originally written to answer two such questions

recently. But as the information became more comprehensive, it became

clear to us that it was too much info for an email. We also wanted to

make this information freely available to anyone searching for it,

rather than limit the information to the members of a single email list

(which has been where a lot of these Question/Answer sessions occur).

Towards that end, we created this web page.

We hope that this page answers most of the preliminary questions that

most folks will have as they consider whether to acquire a livestock

guardian dog. If you, Dear Reader, still have questions beyond what's

listed here, please let us know and we'll add that question, and our

best attempt at an answer, here on this page.

What Constitutes a Livestock Guardian Dog?

Livestock guardian dogs are a group of breeds which were not developed

in the same place, or at the same time, but rather developed in the same

way. These breeds have been created all over the world, in basically

the same ways - breeding dogs over hundreds of generations, always

improving certain characteristics that proved useful when guarding other

animals.

Those characteristics are:

1) very low prey drive, ie, they will NOT chase down prey animals even

when those animals run away (many other dog breeds have medium to very

high prey drive, and will chase anything that moves away from them -

cars, balls, people, cats, etc). Many so-called working dogs do NOT

make good livestock guardian dogs because they are too prone to chasing

down the animals they are supposed to protect. For instance, border

collies, German Shepherds, Australian shepherds and true herding dogs

would make a poor guardian dog. They want to "work" the animals, not

leave them in peace and quiet.

2) Large size. Most livestock guardian breeds are in the 90-120# range

and above. Some females will be at the low end of that scale and some

males for some breeds can go well above 150#.

3) A rough hair coat which gives them good protection from the elements

in which they were bred. Not all dogs were bred for all conditions -

Anatolian shepherds were bred on the arid plateaus of Turkey and Asia

Minor, and as such they are high desert dogs. They can take bitter cold

but don't do well in driving rain. Other breeds such as Komodor could

stand out in a hurricane and hardly notice because their long locks of

hair channel the rain away.

4) Independent and sometimes "stubborn" nature. LGD's were bred to work

remotely, often without any human interaction at all. As such, they

make their own rules, set their own priorities and decide for themselves

where to patrol and how far away to range from the animals they

protect. In more recent usage, they are usually housed much closer to

residences and as such must learn how to be good canine citizens with

basic obedience. They often do extremely well in obedience class in

terms of being calm, respectful and cooperative, and a number of LGD's

have earned various obedience titles. However, when they are working,

they will suddenly develop selective hearing (ie, they ignore commands)

and handle situations as they see fit. Human handlers need to be ready

for this possibility, and be proactive about things like strange

children wandering into the yard, UPS guy coming to the porch, etc.

Should LGD's be raised in isolation, or integrated into family life?

When LGD's were first introduced to the US as a solution for livestock protection, the general recommendation was to limit human handling and leave the dogs at a young age with the animals they were intended to protect. Since then, LGD owners and trainers have figured out that the opposite should be done - these dogs should be well socialized to both human beings and a variety of other animals. This does not interfere with their ability to bond with and protect their flocks/herds. Rather, it prepares them for the reality of modern life, where they are much more likely to come into contact with people, kids, other animals, etc than they were on their ancient territories.

This exposure also helps LGD's form bonds with EVERYTHING in the family - the people, the pets, the livestock, even the friends, family and business acquaintances for any given household, farm or ranch. If any of these individuals have legitimate reasons to visit a property where an LGD is working, then the LGD should be introduced to them in advance, under controlled circumstances. Even people like the UPS delivery person, the meter readers, the post office delivery person, etc, should be introduced to the dog. For those personnel who will only be on the property for a short time, for instance repair or construction people, an introduction under relaxed situations will go far in reassuring the dog that all is well. This can help prevent issues where the dog is uncertain about whether an individual has legitimate reasons to be on the property.

Sometimes we can't introduce visitors in advance, so we just have to do the best we can. There have been several occasions here where we needed to call a veterinarian for emergency care of a sick animal. Under those circumstances, no one is relaxed or casual. Still, try to reassure the dog that no matter what else might be going on, that particular person is needed there, at that particular time.

THis may seem like a tall order, and it is important to make these introductions as often, and in as relaxed a manner as possible. Yet the dogs also pick up on our own body language to help them determine who belongs and who doesn't. When farm vets have visited here for emergency services, sometimes in the middle of the night, somehow our dogs have known they were there for legitimate reasons. They didn't even bark. When we have been inspected by various state agencies, again the dogs picked up on our deference to the inspectors, and were quiet and respectful themselves.

A friend had an interesting story to tell along these lines. While they were building their house, they had contractors in and out and all over the property, for weeks on end. Their several LGD's became accustomed to the many new individuals coming and going. The standard routine was for the general contractor to meet with our friend, and her dogs, upon first arriving each day, and at that time any new employees would be introduced. From that point on, the dogs didn't hassle the workers. Yet one new employee got a different response. Of all the dozens of people working on that project, somehow the dogs didn't like this particular person. They growled, their hackles stood up, and they physically blocked the person from coming on the property. Everyone was very surprised. The new employee was intensely insulted, and walked off the job in a rage. Later, the general contractor found out that particular employee had been recently convicted of small thefts on previous job sites. The general contractor fired him. Somehow, the dogs knew that this person, of all the people on the job site was not trustworthy.

Can Livestock Guardian Dogs Be Trained To Do Obedience, Agility or Therapy Dog work?

Training an LGD is not like working with other breeds. They are not Laboradors, ie easy to train, always responsive, and eager to please. On the other hand, they are extremely intelligent, acutely aware of everyone's demeanor around them (ie they can tell very quickly when someone is nervous, tired, wounded, angry, happy, etc), who is in control of any given situation, and they will readily prioritize a situation to sort out what's important and what's not. So in terms of intelligence, they are very easily trained. But in terms of obedience, they will consider most "commands" to be "suggestions" instead. Many LGD owners talk about how their dogs had perfect obedience manners in the show ring and/or in class, but then won't obey when out and about in public. Most LGD owners believe this is not because the dog is distracted, but rather because the dog is more "on guard" and less likely to be willing to follow a command to Sit or Stay or Come, when there are various potential threats to be monitored. That being said, there are LGD's doing wonderful obedience work, agility competition and even therapy work. These dogs have chosen, for their own reasons, to apply themselves to those tasks. Regardless of how easily any given LGD can be trained, all LGD owners are strongly encouraged to at least complete basic obedience with their dogs, so that the dogs are better canine citizens and so that the owners can effectively handle their dogs in multiple situations.

I've Heard Livestock Guardian Dogs are Aggressive and Dominant

First, let's define the words "aggressive" versus "dominant". They are not the same.

Dominance is the desire to be at the top of the pecking order.

Literally, the "top dog" in the pack. That pack might be other dogs, a

family of humans, a herd of goats, or any gathering of individuals of

any species. The desire to be dominant means that the dog would have

first rights to everything - the dominant animal gets to choose when to

eat, when to drink, where to sleep, where to sit, where to stand, where

to walk, etc. That dominant animal is "alpha", and gets to make all the

decisions. If there is a contest between two individuals (whether that

means two dogs, a dog and a human or a dog and any other animals), a

dominant animal will use any tool at its disposal to "win", whether that

tool is force, intimidation, threats, body language, barking, etc. But

dominance usually does not come down to actual injury.

Aggression, on the other hand, is the desire to inflict damage, for any

reason. It could be motivated by fear - if a dog has been abused, they

might answer future abuse with growling, snarling and biting. If they

are food aggressive, they will guard food by threatening and then

carrying out a threat to do bodily damage if anyone interferes with

their food. These are only two examples - there are many more.

Unfortunately for dogs, they use some of the same body language for both

intentions. If you don't know a dog very well, you might not know that

a growl is a sign of aggression or dominance. Some dogs will seem to

be one when in fact they are the other. Some dogs will do both. But

one rule of thumb is that almost ALL dogs will seek to determine who is

Alpha in any given group, so the question of dominance will eventually

come up. Fortunately, most dogs do not resort to aggression unless they

are threatened with bodily harm, and/or believe that someone or

something they are guarding is being threatened such that they go into

protection mode. Many, many, many dog bite incidents are because human

beings did not understand dog body language, and/or ignored body

language cues that the dog was giving to warn them off.

The question of dominance is one that comes up often. These are

confident dogs, and most will eventually assert themselves and try to

figure out who's actually in charge. That results in subtle and then

more and more direct challenge to every human handler in the family,

sooner or later. Some advocate training them early before they reach

full size, and that's definitely preferable. But most LGD's will begin

to test their limits when they reach full size anyway, and determine

who's truly leader of the pack. The #1 reason for LGD surrender to

rescue groups is that they became pushy and dominant over their human

handlers. This situation can be avoided if the human knows what to

expect, is ready with appropriate training/handling methods, and stays

consistent.

Happily, some very good dog trainers have already worked out a

collection of strategies known as either Alpha Dog Boot Camp, or Nothing

In Life Is Free. These methods are essentially the same thing - a

series of techniques and lessons that will give the human the tools to

take command and stay in command, with the vast majority of dogs (LGD or

otherwise). These techniques work regardless of breed, age, sex or

previous training of the dog in question. They also work regardless of

age, size, sex or experience of the human handler. They are universally

effective. If you are thinking to get a dog of any kind, but

particularly an LGD, arm yourself with either NILIF or Alpha Dog Boot

Camp tools FIRST. Then you'll be in a strong position to answer the

question of who is in charge. Because YOU will be in charge.

Ironically, the stronger the dog, the more they will likely respect that

leadership once it has been established and enforced. For more reading

on NILIF and Alpha Dog Boot Camp, check out the resources listed below,

in the Additional Sources of Information section.

One further note: For those readers who are small-statured, whether male

or female, it is important to say that size is not the determining

issue when it comes to determining who is Alpha Dog. Many

small-statured women have very successfully handled LGDs that outweigh

them 2:1, once those ladies learned how to handle the dogs

appropriately. Children have also learned how to successfully work with

these big, confident dogs. In fact, using force and larger size to try

to dominate the dogs physically is absolutely the wrong approach, and

is nearly guaranteed to provoke further conflict, rather than turn down

the contest. So, if folks can't use size and strength, what approach

should be used?

Some LGD's will never push that boundary. Some push it every single

waking minute. There are a lot of practical things an owner can do to

stack the deck in his/her favor and develop a working relationship with

the LGD such that everyone is happy. See below for some websites which

provide LOTS of info about this. But it's something that needs to be

considered in advance. Once those contests start, it's important to

recognize them for what they are and nip that process in the bud. If a

person is considering an LGD but doesn't want that responsibility (and

it's not like we're talking about police dogs or high levels of

training; just someone willing to be in charge), then LGD's might be

more of a hassle than a help. With a 150lb animal, it's in the owner's

best interests (and the dog's) to learn what that contest is going to

look like, and be ready for it. By reading about it in advance, every

potential owner (man or woman, large or small) can have some strategies

or methods in mind. So when that day arrives, the owner can very

quickly and competently step forward to say "you want to know who's in

charge? I am. You're #2 (or whatever). Now let's get back to work." It

really can be that easy, if folks know in advance what to expect.

How should LGD's be trained to stay home?

LGD's will range far from home if given the chance. Once upon a time this was prudent, so that they could either patrol and find out if predators were in the area, and/or drive them off before they got too close to the herds/flocks. Ranging over a 10 square mile area was a day's work. In today's world of subdivisions, highways and high population densities, all reputable LGD breeders and rescue groups strongly advocate (or flat out require) at least a 5' woven or chain link fence to contain the LGD. That keeps the dogs home where they belong, and out of neighbor's yards, off the highways and out of trouble. You CANNOT train an LGD to simply "stay home". They will push the boundaries of what is theirs until they meet a boundary they cannot cross. All too often, that "boundary" is a neighbor with a gun, an Animal Control officer or a car on the highway. The #2 reason LGD's are turned into rescue groups for adoption is that their owners didn't have adequate fencing, and they wouldn't stay home, regardless of training. Expect that any rescue group or breeder you work with will require a good stout fence to keep them home. If fencing is not an option for whatever reason, LGDs will probably be a LOT of hassle because they'll keep getting out and running off.

Do LGD's work better as guard dogs or as family dogs?

LGD's are often said to be "aloof and uncaring". That is not true. LGD's can form very strong bonds of loyalty, devotion and affection with their human owners, even while also being loyal and devoted to the herds/flocks they protect. The notion that LGD's can only bond with either the flock or the human is utterly false. An LGD in a loving family will form strong bonds with all the members of that family, whether that's a single person or a big family with lots of kids and hundreds of livestock. The LGD will guard them all.

How can I tell if a particular LGD will make a good guardian?

The vast majority of LGD's can successfully be trained to guard anything

- 2-legged kids, 4-legged kids, ducks, chickens, horses, tractors,

gardens, kittens, whatever. If an LGD is tossed out into a field and

left to their own devices, they will pick and choose what they decide to

guard. That choice may not be what was intended by the owner. If they

are handled intelligently and introduced to "their jobs", ie, which

flocks, which kids, which areas, they will learn THAT is their job and

they'll defend it with their lives against all comers. A lot of the

dogs we have rescued (we've rescued 5) were turned in for adoption

because "they wouldn't guard". A few short interviews with their

previous owners found that in every single case, the previous owners

thought they would just automatically "know" what to do, and then didn't

like the choices the dog made in that vacuum of training. All five of

our LGD's have turned out to be fantastic livestock guards, and we

trained them all after they were already adults. That success rate

isn't because we're hotshot trainers. It's simply because we showed

them what we wanted them to guard, and set them up to be successful in

that particular job. There is the occasional LGD which has too high a

prey drive or too aggressive a nature or whatever. That will happen in

any population. But it's extremely rare.

The question here is not one of active training per se, but rather the

owner deciding what he/she wants the dog to protect, then setting them

up to be successful with that job. That usually means setting up either

temporary or permanent housing with their "protectees" so that they can

get used to their protectees over a period of time (usually a few

months) without anyone starting to play so rough that things get out of

hand. We have five LGDs guarding different areas of the farm - one with

the cows/horses, one with the goats/sheep, two with the chickens/small

animals, and one watching the front driveway (really!). So some careful

thought should be given in advance to where the dog will be, what the

dog will be guarding, and whether the dog needs to be protected from the

"protectee" or vice versa. What we've done is set up each new dog near

(but not in) the pen or yard they will eventually guard, such that the

dog can watch them all day every day. Then throughout the day, we get

the dog used to the people, animals, events, vehicles etc which will be

coming and going as part of normal business. That includes introducing

people (like the vet) who might be in working with the animals being

protected. Nothing makes a vet crankier than being bitten on the butt

by an LGD while working on a goat. If the dog is going to be in a home,

give the dog an area (like a kennel or crate) which he/she can retire

to, eat in and otherwise be in without being hassled by kids or other

pets. And provide lots of walks around the perimeter of the area to be

guarded, even if that's only a backyard. By setting the boundaries the

schedule and the expectations early, the LGD will sort out right from

wrong much, much more easily.

People say LGD's should be obtained from a breeder raising them with livestock, in order to make sure they learn how to guard livestock. But then I hear about rescue groups trying to re-home older dogs. Which source is better?

The question sometimes comes up about whether to get an LGD from a

breeder, or a rescue organization. There are pro's and con's to both. A

breeder can give you information about their parents, can provide good

handling right from birth, can raise them with livestock so they are

already accustomed to the animals, and provide a solid foundation of

learning in a safe environment. Those breeders put a lot of work into

their dogs and their pricetag reflects that. If you want to work with a

breeder, they should be willing and able to provide references for

other families who have purchased dogs from them. Talk to those

families and see if the breeder continued to provide support,

encouragement, answers and information as the family got used to the new

dog. If the breeder does not show much interest in how you'll be using

the dog, the type of home it's going to, and/or doesn't want to be

contacted after the sale, keep shopping for another breeder.

Rescue organizations can sometimes give a lot of information about a

dog, but sometimes no details at all. However, they often do at least

preliminary testing with each dog to determine the personality traits,

flush out big problems, etc. Most LGD's are turned in for adoption

between the ages of 18-30 months, so they have most of their working

lives ahead of them. While any dog from any source should get basic

obedience training, these older dogs are often much easier to handle.

They are more settled and have outgrown their goofy puppy stage where

they destroy everything and need constant attention. Most rescue groups

have extremely stringent adoption policies, for the simple reason that

they don't want the dog to be adopted out only to have that adoption

fail. Every rescue group I've ever worked with will try to work with a

family where a dog was placed, and solve any problems that come along,

but they will take a dog back if the adoption doesn't work. The only

exception to that is in the case of a dog biting a human being. Most

states now have a one-strike-and-you're-out clause where rescue groups

cannot adopt out a dog that has ever bitten a human being. That's why

they work so hard to make sure that adoptions work, and the dogs are in

good homes with good training so that bites are less likely. That's a

sore point right now, because a lot of good dogs are put down after a

bite that was totally justified. But whether folks agree with it or

not, it's the law that those rescue groups must work within. Cost for a

dog from a rescue group is usually much, much less than from a breeder,

even when these animals are purebred and registered (three of our five

were purebred with papers).

I've heard that LGD's bark a lot. Can that be controlled?

Another issue with LGD's is barking. An LGD's first line of defense, to tell the predators to just keep on moving, is to bark. LGD's have a large vocabulary of barks, from sharp warning barks about an intruder, to long drawn out howls at the moon (yes, one of our LGD's regularly howls at the moon), to yippy barks of excitement (oooh, it's dinner time!), to snarls and growls that would make you think you just brought home Cujo. Barking is another major reason why LGD's are turned over for adoption. That barking will max out during the first year the dog is in a new home, with most dogs gradually decreasing their barking until they only bark when they need to drive away an actual predator (but with a few bellowed "yes, I'm still here" to the world scattered throughout the rest of the day). And this isn't normal barking. This is a big booming sound that can be heard 1/4 mile away. Some folks like that sound, because it tells them that Mr. Dog is on duty for the whole neighborhood. But lots of neighbors do object. With our 5 current dogs, we have had to come to something of a truce with our neighbors that the two biggest barkers are on duty during the day, and the three least-likely-to-bark are on duty at night, just so that everyone stays sane. Have that conversation with neighbors now, rather than after everyone's ticked off because of all the racket. For the rest, we have used the "day duty vs night duty" rotation to keep the peace.

Additional Sources of Information

The above questions are those which are usually the first to be asked

when someone is either considering acquiring a livestock guardian dog,

or has begun having problems with their dog. We strongly encourage

potential owners to review the following websites so that they are as

fully educated about their potential dog as possible. For those owners

already facing some behavioral problems with their dogs, we encourage

owners even more to review this information, so that the dogs can be

worked with and kept in the household if at all possible. There are

already a great number of dogs being put up for adoption, and most

rescue groups have more dogs than adoptive homes.

www.lgd.org. This website is possibly the single best source of information about all aspects of livestock guardian dogs around. The Library

page at that website is a compendium of excellent articles, by various

authors, which detail the Nothing In Life Is Free and Alpha Dog Boot

Camp philosophy and techniques. Whenever we need a quickie review of

these techniques, this is where we get it.

K9Deb's NILIF page is another

excellent summary of not only the philosophy and techniques, but also

what to expect when you start using these techniques on a dog for the

first time.

Who's In Charge Here?

is an article written by by Vicki Rodenberg De Gruy, Chairman of the

Chow Chow Club Inc.'s Welfare Committee. It is an excellent explanation

for the Alpha Dog Boot Camp philosophy. Her work is quoted elsewhere,

including on the LGD.org website, but here it is individually.

Further Questions, and One Last Note

If either this website and/or the above additional websites do not

answer your questions, please feel free to Contact Us and we'll do our

best to answer your questions, then post that additional information

here so that others will be able to benefit.

These dogs can be a lot of work, but they are worth that work to become

the fantastic partners they were bred to be. All our rescued livestock

guardian dogs have become priceless partners for our work here. We wish

you the same experience with yours.

Livestock Guardian Dog Books

Sponsored Links

Our Successful Farming and Ranching Books

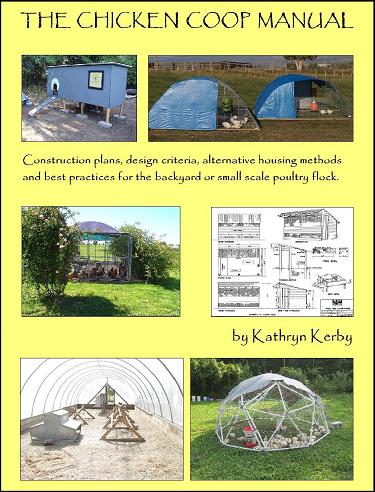

We released our very first self-published book. The Chicken Coop Manual in 2014. It is a full color guide to conventional and alternative poultry housing options, including 8 conventional stud construction plans, 12 alternative housing methods, and almost 20 different design features. This book is available on Amazon.com and as a PDF download. Please visit The Chicken Coop Manual page for more information.

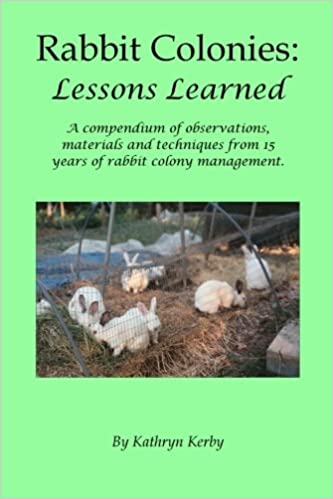

Rabbit Colonies: Lessons Learned

We started with rabbits in 2002, and we've been experimenting with colony management ever since. Fast forward to 2017, when I decided to write another book, this time about colony management. The book is chock-full of practical information, and is available from both Amazon and as a PDF download. Please visit the Rabbit Colonies page for more information.

The Pastured Pig Handbook

We are currently working on our next self-published book: The Pastured Pig Handbook. This particular book addresses a profitable, popular and successful hog management approach which sadly is not yet well documented. Our handbook, will cover all the various issues involved with pastured hog management, including case studies of numerous current pastured pig operations. If you have any questions about this book, please Contact Us.