Management Alternatives for

Small Scale Swine Production

Overview

Pigs have been raised intensively for many generations, in many ways and for various reasons - economics, geography, nutrient

management, social tradition and/or agricultural convention. The modern method for intensive swine production is in climate-controlled, confinement housing with easily-cleaned concrete floors, or slatted floors with retaining chambers beneath for urine and manure. The waste material passes through the slats, leaving the pigs relatively clean and sanitary. However, hogs maintained in this type of housing can develop a variety of either acute or chronic health issues, and many consumers object to such unnatural conditions. Happily, there are a variety of much more natural alternatives. Some are quite old, dating back hundreds or even thousands of years in various parts of the world. Other approaches have been made possible, or at least more practical, by modern small-scale

equipment, methods and materials. On this page we'll explore some of them and how they can be used on small farms today.

History and Options

Domesticated pigs are believed to have originated with the Eurasian wild boar. Pigs were domesticated repeatedly throughout history, in different ways, starting from slightly different genetic lines native to different geographic areas. Both the wild ancestor and domesticated descendant are amazingly adaptable to a variety of environments, ranging from tropical rainforest to temperate farmlands. Their adaptability, feed conversion efficiency, omnivorous nature and generous reproductive capacities made them a valuable livestock candidate for colonization efforts around the world. They were, and continue to be known as, mortgage-lifters because of these qualities.

To reach that potential, farmers and livestock owners have tried a lot of different housing arrangements over the years. Without

trying to catalog them all (and there are dozens if not hundreds of specific methods), several complementary methods have emerged

as having very good potential for modern small-scale owners:

1) hoophouse, pole barn or porta-hut management, often in combination with deep bedding systems

2) pastured management, either seasonal or year-round, with the pigs harvesting at least some of their own feed via foraging,

browsing and/or grazing

3) forest/woodlot management, either seasonal or year-round, with the pigs again harvesting at least some of their own feed via foraging, rooting and browsing.

Our own hogs, and those of most fellow hog owners, follow one or more of these methods.

Advantages

Hogs are prodigious foragers, and should be allowed to harvest their own feed if at all possible. A wide variety of wild or in-the-field plants, invertebrates, and even birds and small animals, can provide a considerable supplement to bought-in or cultivated and harvested feeds. Specifically, most root crops, many nut crops, many grain crops, many mushrooms, and any small animals or insects which the pig can capture, can provide a rich nutritious diet with little to no cost or labor for the owner. That feed offset might only be minor or it can form the entirety of the diet, depending on the diversity and balance of local materials.

Another benefit for any of the three above behaviors is that pigs can be housed in species-appropriate social groupings. One such natural group would be a sow and her piglets, kept together at least through weaning and possibly longer. Another such natural grouping would be weaned piglets not yet ready for market, after the sow has been separated out for further breeding or market. Bachelor groups of males can sometimes be kept together as long as in-estrous sows are not within range of their very sensitive senses of smell. Young gilts and even mature sows can be housed together as a batch, and either allowed to choose individual nesting areas when the time comes, or separated out only when about to deliver their next litter. These social groupings may seem low priority but they can dramatically reduce the stress and subsequent illnesses often encountered in confinement operations.

A third benefit is the much-less-expensive costs for housing afforded by any of these three methods. Hogs generally need very little in the way of shelter during most weather conditions. They are prone to sunstroke, so need both shade and either cool soil, water or wallows to keep their body temperature down and prevent sunburn. They are much less prone to cold weather, but their ears can get frostbite in very cold clear weather or duing extreme windchill events. They also do poorly when a combination of wind, cold and precipitation keep them covered in moisture during cold weather. Happily, those requirements are relatively easily provided for.

Home-made or purchased porta-huts or calf sheds have worked very well for many hog raisers, for either full-grown adults or litters of young ones. Hogs in open country will seek shelter under trees, behind wind breaks, or in self-excavated hollows. Possibly best of all, hogs will build ample nests given any sort of grass, hay, moss, or forest litter. They will sometimes choose these nests out in the open, rather than warmer and/or drier manmade housing. One very cost-effective way to combine on-farm materials is to provide an inexpensive roof made of any material (sheet metal, plywood with roofing, hoophouse film or even cloth or plastic tarps), with generous bedding beneath. If long periods of windy and/or cold weather are expected, adding a simple windbreak (plywood, straw bales, or even a haystack) can make a very low-cost, yet effective and comfortable place to bunk down and ride out the worst of winter. The main thing to be aware of here is that most pigs will take great delight in rebuilding their nests frequently, which translates into a lot of destruction if those materials are not stout, protected and/or well secured. More about that in the next section.

A fourth benefit of these low-tech and low-cost methods is that they can be used when appropriate on a seasonal basis and changed or modified almost indefinitely, without the capital costs involved with more complicated barns or buildings. For example, a simple box stall can be bedded down in winter with plentiful straw and the pigs kept inside during the winter. Then when the soils dry out in spring, they can be housed on pasture through the growing season, and allowed to graze or browse either the native pasture or crops planted specifically for them. Or hogs can be turned loose in fenced woodland during spring, summer and/or particularly fall to glean whatever wild foods they can find, yet bed down in a relatively small porta-hut with bedding.

One last benefit may or may not be of value on any given farm, but it has been of great value to us. Namely, a pig's tendency to clear land. On our property that has been a marvelous benefit because our woods are badly overrun with a wide variety of thorned brambles. I can and have repeatedly cut those brambles back, only to have them return in a matter of months. But put pigs out in that same area, and they'll eat the vines, root up the root nodules, and keep the area clear until moved to some new area. Combine that with generous bedding, and they essentially become terraformers. They have repeatedly cleared new garden areas for us and for that, I'll be eternally grateful.

Disadvantages

These low-tech approaches have few disadvantages, but several things should definitely be remembered. First of all, pigs will rarely jump over a fence but they will happily go under, or try to squeeze through gaps. They are very easily trained to hotwire, and often a single strand will contain them. When turning pigs out in either field or forest conditions, that single strand of hotwire can ensure that you find them exactly where you left them. And frequent hotwire testing will ensure they stay there until you are ready to move them. Without hotwire, your fencing will need to be MUCH stronger than it would otherwise.

Secondly, hogs are as hard on housing as they are on fencing. And like with fencing, they will chew on and shove against the lower edges of walls, often blowing out the joint between wall and floor unless both are extremely stout. Even with bedding in place, a hog will sometimes dig down through the nest, hit the floor or wall, go to the nearest corner, and keep working that corner until they have chewed or simply shoved through. For buildings without flooring, the hogs can and will dig down below the foundation and sometimes lift the wall right off the foundation. Sometimes only by a little, but sometimes enough to break the building's structural stability. As a result, windbreak materials should either be easy to replace, protected by hotwire, or absolutely dig-proof and root-proof (such as concrete).

Third, pigs will dig. They will dig enthusiastically, deeply and rarely in the direction or depth you were hoping for. Pigs turned out on high-value pasture can browse that pasture nicely for awhile, and seemingly pose no threat, then start to rip it up one day and not stop until there's no a square yard of level turf left. They will do the same in forested areas, and take great delight in uprooting trees. Some say they do it because of the bugs found in the rootball, while others say they dig up trees simply because they can. I suspect it's a bit of both. Now that ability can definitely come in handy if you want to remove those trees, but they aren't choosy. They're just as likely to take out the high-value tree first and leave the old dead one alone. If you want to keep your trees healthy, watch for digging behavior at the base of the trunks and move the pigs if they start going after trees you want to keep.

Fourth, pigs are notoriously stubborn about being moved, and raising them in field or forest generally gives them more opportunity to refuse to go where you want. They cannot be herded like other livestock, and they are too heavy to force where you want to go. The moment you need to lead them somewhere, whether that be the next field or back to the barn or into the trailer, you'll quickly learn that pigs will only go where they want to go and there's precious little we puny people can do to convince them otherwise. Many of the old books talk about putting a bucket over their head to drive them backwards. Having tried that method myself and having swapped notes with several others who have tried, the result was usually me on my butt holding onto an empty bucket and the pig barreling off in some other direction. Sadly, physics is almost always on their side. Or maybe modern pigs just don't like buckets. A much, MUCH more efficient method is to simply train pigs to come when called, and to go into locations or buildings or trailers

frequently, such that when you NEED them to go in it's not a big deal. Training pigs is not difficult; they are very quick to learn (sometimes too quick) and they respond extremely well to positive reinforcement. A bit of grain, a favorite cracker, or some sweet pastry can be used to get them to cooperate a few steps at a time. Once they learn that they'll be rewarded to coming to you, most (but not all) herd movements can be dramatically simplified. However, they will resist going into new or scary environments, regardless of how many treats you have in your hand. On the flip side, if there's no browse left in their yard and/or you're trying to bring them in after an escape, no amount of treats may be enough to lure them back. My neighbors still chuckle about the day one of our gilts got out into our woods, when all the nuts were ready for gleaning, and it took me four hours, some tracking skills I haven't used in decades, and a long rope to get her back into the yard. I was lucky she was good-natured enough that she let me tie the rope around her harness style, with a loop around her heart girth and another loop around her neck. But even with our good working

relationship, I couldn't simply drag her back. I had to wait until she started moving in the direction I wanted her to go. As long as she kept moving in that direction I let her continue. The moment she turned, I stopped. Yes, she did drag me a bit, but we eventually got back to the yard after much squealing and cussing. I won't divulge which of us was squealing and which of us was cussing. If your pigs ever get out, you'll figure it out easily enough.

Finally, pigs cannot be allowed to access either natural or man-made water sources. They simply do too much damage otherwise. For moving water like creeks and rivers, they will destroy existing ramps, root out hollows under the bank allowing for future bank collapse, and can utterly destroy dams or breakwaters. For still waters like ponds and lakes, they will destroy the bank, kick up the sediment at the bottom, and generally "help" that sediment migrate towards the deepest part of the pond. There's an old saying that when you give a pig access to a 1/2 acre pond 4' deep, you'll end up with a pond 4 acres wide only 1/2' deep. Fence them out and give them water separately. Do whatever you need to do to keep them out of waterways. Or you'll end up with their very favorite place - a permanent muddy wallow.

Our Experiences

We have kept our pigs in the woods year-round for some time now, using small porta-hut type shelters as protection from the worst

weather. For fencing, we've used standard 4' field fence with a single strand of hotwire about 12" above the ground. For 99% of that time, we have been very happy with this arrangement. That 1% disatisfaction has come from the frequency with which we've had to rebuild their porta-huts. When we first brought them home as little weaner pigs, we used a calf hutch that served them extremely well for that first year. We needed minimal bedding to keep them toasty and warm through even the coldest winters, and they loved it. But as they grew, they outgrew the shelter, and several of our next huts proved very short lived. Now that we have piglets on the way, we are about to set up a much larger shelter to not only house the two sows but also their piglets, while also providing us with some stand-up space to check on our porcine families throughout the year. That shelter will be 20x20, with farrowing spaces, outdoor access, a small work area for us, and best of all - hotwire around the perimeter so that our beloved hogs don't destroy it. We'll post photos of that next-generation building when we get everyone moved in.

For Further Information:

There is a tremendous amount of information out there for small-scale, cost-effective hog management. Here are some of those

sources; we encourage you to look for and check out any others you may find.

Sugar Mountain Farm - pastured pigs in Vermont, USA

Combining the best of Swedish deep bedding and crated farrowing for winter production

A Two-litter Pastured Farrow-to-Finish Budget

Pasture-Based Swine Management

Outdoor Pig Production in Western Iowa

Iowa State's Outdoor Pig Production - An Approach that Works

Journey To Forever's Pigs for Small Farms

Pre-Confinement Era Swine Texts

Forested Pig Production

Survey of Pig Production Methods in Colombian Rain Forests

Our Successful Farming and Ranching Books

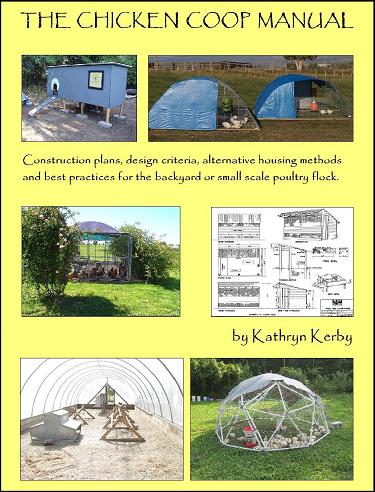

We released our very first self-published book. The Chicken Coop Manual in 2014. It is a full color guide to conventional and alternative poultry housing options, including 8 conventional stud construction plans, 12 alternative housing methods, and almost 20 different design features. This book is available on Amazon.com and as a PDF download. Please visit The Chicken Coop Manual page for more information.

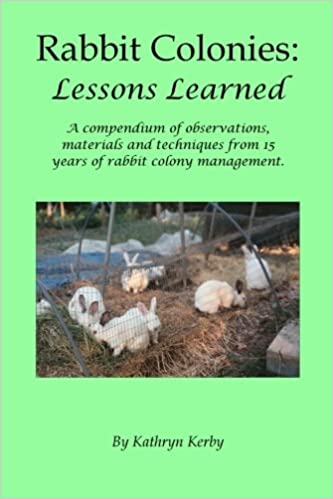

Rabbit Colonies: Lessons Learned

We started with rabbits in 2002, and we've been experimenting with colony management ever since. Fast forward to 2017, when I decided to write another book, this time about colony management. The book is chock-full of practical information, and is available from both Amazon and as a PDF download. Please visit the Rabbit Colonies page for more information.

The Pastured Pig Handbook

We are currently working on our next self-published book: The Pastured Pig Handbook. This particular book addresses a profitable, popular and successful hog management approach which sadly is not yet well documented. Our handbook, will cover all the various issues involved with pastured hog management, including case studies of numerous current pastured pig operations. If you have any questions about this book, please Contact Us.

Weblog Archives

We published a farm blog between January 2011 and April 2012. We reluctantly ceased writing them due to time constraints, and we hope to begin writing them again someday. In the meantime, we offer a Weblog Archive so that readers can access past blog articles at any time.

If and when we return to writing blogs, we'll post that news here. Until then, happy reading!