What's In a Label?

May 2, 2011

We have generally followed organic practices since our farm’s inception, but we have never been certified organic. We haven’t gone through the certification process for several reasons:

• some of our specific practices and facilities do not meet the detailed criteria of the National Organic Program (NOP)

• the record-keeping requirements are useful and well intentioned, but I’d have to give up sleep in order to keep up with all that documentation

• I have been concerned about our livestock’s health care options under the NOP rules.

So when we are asked about whether we’re certified organic, we cannot say “yes”. Nor can we use the word “organic” in any of our marketing information, on our farmers’ market signage, or on the website. Under current USDA NOP rules, the word “organic” cannot be used unless producers are certified. We can, however, explain that we follow most of the NOP crop-management and animal-management guidelines. Sometimes that explanation is enough. Sometimes it’s not, and folks ask us why if we’re so close to meeting organic standards, we haven’t gone the last few steps. It gets to be a frustrating conversation when I have to explain that I already have 30 hours of work to squeeze into each 24 hour day, let alone adding the NOP’s additional requirements.

Now, to be sure, that certified organic designation is not the only game in town. There’s also Certified Naturally Grown. That program is a much less formal entity, and it is not regulated or controlled by any federal government agency. The Naturally Grown standards are taken largely from the NOP, but with specific changes made along the way. Some of those changes are more strict than NOP guidelines. Some are more flexible. The record-keeping requirements are much less stringent, which is both a plus and a minus (easier on the day-to-day production requirements, but also allowing for items or practices that would not pass muster if examined later). I have circled around this option for awhile. The part I can’t get past is that a farm can be certified Naturally Grown if it claims to meet the criteria, and is then inspected by any person who is already certified Naturally Grown. But the knowledge, competency, fairness, thoroughness and diligence of that individual are appropriate only so far as their own personal working experience. For instance, a recent check of the CNG website

s “find a farm” map, identified almost a dozen farms within two hours’ radius of us. Two of them were apiaries, nine of them were produce-oriented, and only one was livestock-oriented. None of them, as far as I could tell, featured all three operations. So whoever did my inspection would only be familiar with one third of my operation. That makes me really uncomfortable. Perhaps there are ways in place to deal with that scenario but so far I haven’t found those alternative criteria. So I mull and I debate with myself, but so far I haven’t gone that route. Yet I get that “why not?” almost as often as the question about being certified organic.

Two more terms have also recently come into more frequent play, namely “local agriculture” and “sustainable agriculture”. While local agriculture would seem the clearest and most easily defined of the two, even that term has issues. First of all, what constitutes “local”?? Is it food produced within 5 miles of home, within 50 miles, within 500 miles, or even further? An arbitrary national definition could be imposed by the USDA or some other agency, but that would almost certainly violate more practical definitions based on geography and cultural boundaries. For instance, let’s say that local production is defined as 100 miles. The distance between Everett, our county seat, and the southern Washington state border is roughly 150 miles as the crow flies. Yet it’s only roughly 100 miles between Everett and Wenatchee, county seat for the county just east of us. So it would seem by looking at a road map that Wenatchee would be considered a “local” market for us, while towns near the southwestern border of the state would not be local. However, anyone living here would quickly recognize that we have much more in common with folks in that southwestern corner of the state - in terms of regional culture, climate, agricultural production and even market opportunities, than in Wenatchee. This is because a mountain range stands between us and Wenatchee. That mountain range has created something of an informal but very real boundary between eastern and western halves of the state. Folks in eastern Washington are fond of thinking that we’re simply an extension of California. Folks in western Washington dismiss the eastern half of the state as being more akin to Idaho and Montana. If we tried to sell in Wenatchee, we’d have a tough job of it. Selling to someone in the southwest corner would be simple by comparison. So “local” is as local does. Once again, the definition of the word eludes simple description.

”Sustainable” isn’t much better. There’s economic sustainability, environmental sustainability, and even ethical sustainability, and variations within each of those. For instance, one measure of economic sustainability would indicate that a farm must simply bring in more income than it spends. Sounds simple enough. But if a farmer pays himself next to nothing in the attempt to show a profit, and operates so close to the margin that he has no savings account or retirement plan, is that economically sustainable? Or consider environmental sustainability. A farm could meet every certified organic rule and regulation on the books, yet still contribute to loss of biodiversity, loss of disease resistance in flocks, herds and plant varieties, or even still rely on bought-in substances to provide for ongoing soil fertility. And the farmer who runs his farm very conscientiously by economic and environmental standards, yet runs his or her employees into the ground, can hardly be considered sustainable. So there’s no easy definition there either.

What’s a farmer to do, as we try to carve out some way to define and describe what we do? And what’s the consumer to do, when trying to evaluate different farms?

The only answer I’ve been able to come up with so far, and the best suggestion I can make, is to educate, educate, educate. Educate ourselves not only on the details of how to run our farms, but also on the short-term and long-term, local and global implications of our actions. Educate ourselves on the issues surrounding genetic diversity, livable wages, reliance on fossil fuels and petrochemicals, or even the pro’s and con’s of heirloom vegetables and heritage livestock breeds. We as growers and livestock owners need to educate our consumers, because no one comes into the marketplace as either buyer or seller, knowing all this stuff in advance. And consumers need to educate themselves because there is no one right answer; each farm and each producer has a mix of conditions which warrant flexibility. In short, we need to talk to each other - producer with consumer, regulator with permitee, employer with worker. I think that’s the only way to have farms that work well today, and will continue to work well tomorrow. In fact I sorta doubt any other recipe would suffice.

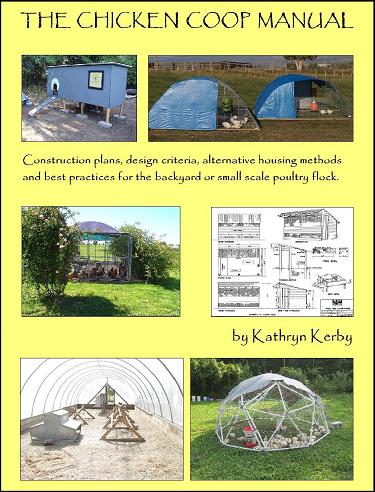

Our Successful Farming and Ranching Books

We released our very first self-published book. The Chicken Coop Manual in 2014. It is a full color guide to conventional and alternative poultry housing options, including 8 conventional stud construction plans, 12 alternative housing methods, and almost 20 different design features. This book is available on Amazon.com and as a PDF download. Please visit The Chicken Coop Manual page for more information.

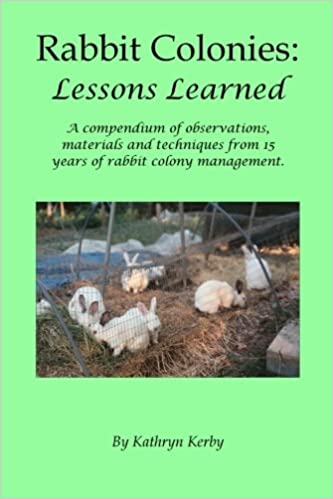

Rabbit Colonies: Lessons Learned

We started with rabbits in 2002, and we've been experimenting with colony management ever since. Fast forward to 2017, when I decided to write another book, this time about colony management. The book is chock-full of practical information, and is available from both Amazon and as a PDF download. Please visit the Rabbit Colonies page for more information.

The Pastured Pig Handbook

We are currently working on our next self-published book: The Pastured Pig Handbook. This particular book addresses a profitable, popular and successful hog management approach which sadly is not yet well documented. Our handbook, will cover all the various issues involved with pastured hog management, including case studies of numerous current pastured pig operations. If you have any questions about this book, please Contact Us.

Weblog Archives

We published a farm blog between January 2011 and April 2012. We reluctantly ceased writing them due to time constraints, and we hope to begin writing them again someday. In the meantime, we offer a Weblog Archive so that readers can access past blog articles at any time.

If and when we return to writing blogs, we'll post that news here. Until then, happy reading!